OldSpeak

Whose Art Is It Anyway?

By Neal Shaffer

May 30, 2003

This July, San Francisco's Museum of Modern Art will play host to an exhibit of "Illegal Art"—works that have aroused or could arouse, for one reason or another, legal action. The works range from a skewering of the Starbucks logo to Negativland's infamous "U2" album cover. The styles and media vary widely, as does (to be fair) the intensity of the responses they've garnered. But when taken together they make for a compelling assemblage, one that raises some critical questions about the role of the creative artist in the age of marketing, and to what extent the law is, and should be, involved.

|

The very idea that the need exists for such an exhibit ought to throw up a series of red flags. While there is no prescribed role for art in any given culture, there can be no debate over the fact that it serves a needed function. Often, and thankfully, the function is that of gadfly. Explicitly political speech is often too easy to demonize and, thus, ghettoize. Witness Michael Moore's Oscar acceptance speech—a misguided attempt at soap-boxing that subjected the entire anti-war movement to needless ridicule. This is not to say that political speech should be discounted or minimized, but that the particular gifts of the artist can often be put to powerful subversive use in achieving ends that simple statements, and even debate, often don't.

|

What the curators of the Illegal Art show don't mention explicitly, though it is implied, is the influence and power of corporate brands, and the lengths to which companies will go to establish and protect them. It's an issue that receives disturbingly little attention given just how powerful an influence it is on our daily lives. While it's easy to attack American corporate culture for excesses and evils (and the process is rightly ongoing), those critiques generally stick to overt and obvious cases, such as Halliburton profiting from the Iraq war. But the brand culture exerts a surreptitious influence on ordinary citizens in a far more nefarious way.

Barnes and Noble, just one exceptional example, employs this process to such a degree that every fixture and display in any given store is organized from on high by a gigantic monthly planning document that is shipped to each and every outlet. Individual employees must follow this plan to the letter to ensure compliance with the brand, and ensure a fully manipulated and directed experience for the consumer.

|

It is certainly the prerogative of the corporation to do business as it sees fit, but the shame of it is that average consumers are not aware of the extent to which they are being controlled. Most shoppers probably don't know, for example, that some chain music stores classify their outlets according to the demographic they serve. One major mall chain even went so far as to employ a classification dubbed "Urban/Street Flava" for their stores that served a predominantly African American crowd. It's all in the name of marketing the brand, but how would the targets of that process feel about being treated as just so much predictable cattle?

|

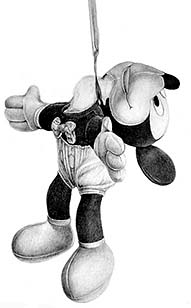

Theoretically, of course not. Satire must remain protected speech if there is any hope for a culture to advance. But the problem that a corporation like Starbucks—or Disney when Mickey Mouse is used to satiric effect—has with such works is that they have the very real potential to alter the public perception of the brand. Symbols are a dangerous way to make a living, but the brand culture has thrown its weight behind their use so fully that any small attempt to tweak it must, if the brand is to be preserved, be defeated.

DISCLAIMER: THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN OLDSPEAK ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE.