OldSpeak

Tools of Their Tools: On Luddites, Frankenplants, and Nicols Fox's Against the Machine

By Jayson Whitehead

June 11, 2003

"But lo! Men have become the tools of their tools."

—Henry David Thoreau

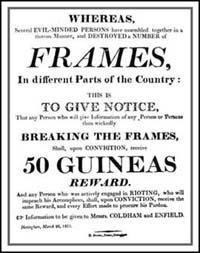

In the early 1800s, a young apprentice weaver in England named Ned Ludd was said to have smashed a knitting machine that he refused to operate. He was just one of many artisans, craftsmen, and laborers that were beginning to oppose the wholesale introduction of machines to do jobs that individuals had done for hundreds of years. As workers' frustrations mounted in the face of unemployment, their ire focused on the early structures that were making them expendable. Across England, groups of displaced workers broke into shops and destroyed shearing frames and other such machines. In 1811, a thousand men marched into a town called Sutton and broke between thirty and seventy frames. These violent actions were becoming known as the "Luddite Rebellion," and as they continued, British authorities responded with a piece of legislation called the Frame Breaking Act that provided for the death penalty in cases of machine breaking. With thousands of troops committed to quashing the Luddites, numerous men were arrested, and within a year of passing the legislation, over 20 men had been hung. The Luddite rebellion was effectively over.

"Luddism at its core," writes Kirkpatrick Sale in Rebels Against the Future, "was a heterogeneous howl of protest and defiance, but once that cry was heard in the land and the only response of officialdom and merchantry was indifference, indignation or inhibition, it hardly knew what to do, how to continue, where to move." The Luddite rebellion had in fact failed. The machines and the factories to house them kept coming. The Industrial Revolution was on. Yet, the group of people that were known as Luddites initiated something that continues to this day. As Nicols Fox writes in her recent book Against the Machine:

Although it has roots far back in history, there is, in fact, a consistent thread of thinking about humans and technology that begins around the time of the Luddite Rebellion and continues without a break up to the present. Resistance to the domination of the machine has branched into the arts, nature, agriculture, labor, politics, and spirituality. Follow those connections, and a continuing tradition of thought and art and action begins to emerge. And with it comes the revelation that those who are concerned about technology are not alone; have never been alone.

***

Nicols Fox pinpoints the origin of her affinity for an agrarian way of life to her youth and the time she spent with her grandparents in rural Virginia. "In the late '20s/early '30s, my grandparents ravaged a falling down log barn and constructed a log house in the Shenandoah Valley," she says. "They'd gone to great lengths to have a beautiful, authentic stone fireplace, in which there were all the old iron things for cooking over the fire, and the beams were all exposed inside. It was just a fabulous place."

Fox spent most of her childhood summers in this idyllic scene. Her great-aunt had done much the same thing as her grandparents, settling less than a mile away. Fox and her cousins frolicked through the pastoral setting. "We had free reign to run and do exactly as we pleased in this natural environment," she recalls. "You could ride ponies, you could climb the cliffs across the creek, you could spend hours poking around in the creek. We were as free as birds. It was wonderful to be in that environment."

Today, the sixty-year-old author has exchanged the rolling hills and lush pastures of Virginia for the wooded coast of Maine, where she runs an independent bookstore called Rue Cottage. That is, when she's not writing. She is the author of Spoiled and It Was Probably Something You Ate, two books that address the problem of foodborne illness. She also frequently contributes to a number of publications, including the New York Times and the Washington Post. Her newest book, Against the Machine: The Hidden Luddite Tradition in Literature, Art, and Individual Lives, traces the theme of Luddism from its inception in the early 1800s up to present time.

***

While the term "Luddite" originally sprang from the armed resistance to textile machines, today's meaning can be broad, and is usually used to describe anyone who resists technology. In the current atmosphere, "Luddite" also often carries a negative connotation. Why wouldn't you want a phone that can take and send pictures or a car with a TV? "I think today it is used in the sense of being foolishly resistant to technology," Fox says. "It's a term of derision. People say, 'I'm no Luddite, but....' And they apologize for something they're holding out against."

Fox is pleased to take on the Luddite mantle, and frequently boasts of her resistance to technology. "The tyrannical nature of the computer just goes beyond anything we've ever experienced before," she says. "There are obvious things: as a writer, unless I was 92 and hugely famous, I would be expected to send in my manuscript on a disk. And of course we won't even go into what that's done with prose. But the tyrannical nature of the computer is in other things. For instance," she says, with exasperation clinging to every word, "I have some new books I order for my store when I can't get old books on a particular subject I want. And the book distributor I was ordering them from informed me that I could no longer get the same discount if I ordered them over the phone. I would have to order them over the Internet." After it took her over two hours to do what would normally only cost her 10 minutes, Fox switched distributors to one that would still allow her to order over the phone. "But I'm looking at the fact that maybe in two or three years, they're going to say the same thing," Fox bemoans. "'You can't get the discount unless you do this by computer.'"

Fox's refusal to accede to the every whim of technology illustrates both the nature of a modern Luddite and the harsh reality of her stance. By necessity, almost any Luddite action involves a single individual or a small group resisting a much larger force. As a result, any rebellion must generally measure its successes against an overall loss. "There have been small victories," Fox says, "but [they] are rare indeed. I think it becomes very, very difficult to resist in this day and time, and sometimes I almost despair," Fox admits, before turning to Ned Ludd and his disciples for inspiration. "On the other hand, we're still talking about the original Luddites. So, in a sense, they've been quite successful, because we still use their name to describe those who put up some kind of resistance."

|

The rising opposition to the industrial revolution in England coincided with an artistic movement called Romanticism that was populated by poets like William Wordsworth, Lord Byron (who fought the Frame Breaking Act in Parliament), and William Blake. In Against the Machine, Fox links the Romantics, who put an emphasis on the human spirit and the glory of nature, with the Luddite movement and its anti-machine stance. "The machine has no spirit," she says. "The machine is dead, and humans are alive. I don't think those are over-simplified terms."

The Romantic movement precipitated a similar cultural revolution in America, led by such luminaries as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, and Henry David Thoreau, whose yearlong stay in a cabin, self-immortalized in Walden, has become the emblem of a Luddite lifestyle. "[Thoreau] says throughout Walden that he was trying to find a way to live as cheaply as possible so he could write. He was not a recluse, he was not anti-social," says Fox. "He understood that getting rid of things was important. Obviously his association with nature was important. He was a person who took charge of his own life. He did what he needed to do, when he needed to do it, and he did so with a wonderful affection for nature, and a fabulous talent for expressing what he was experiencing, and being able to share that with others," Fox says. "So, he's a great gift for us in many ways. But it's that taking charge of one's life that's important, and not letting other people be in charge of it."

With that in mind, Fox is quick to point to an area where she sees positive change happening, albeit at a glacial pace. "It doesn't come through legislation usually, but it can come through consumers making choices," she says. "For instance, in the past thirty years, we've seen organic foods go from nothing to a significant portion of food purchased. And that's come about by individual people making choices. So I consider the resistance to corporate and industrialized food as a Luddite gesture as well. You're not just looking for clean food, you're sometimes looking for a sustainable agriculture, or an agriculture that seems more traditional and healthier."

Fox has written at great length about foodborne disease in her two books, Spoiled and It Was Probably Something You Ate. The first book focused on emerging foodborne pathogens, and her research led her to make a general inquiry into the harmful effects technology can have in overall nature. "It started off with my interest in a new pathogen in our food supply, E-coli 015787, and I was just fascinated by the idea of where it came from," she says. "We have this pathogen in cattle because we changed the way they're fed. We tried to make them grow faster, so we gave them protein. Well, cows never ate protein, they ate grass, and their bodies aren't designed for this, so it creates acid. E-coli 015787 has probably always been around, but it's resistant to acid, so while other bacteria are killed off, it survives and thrives."

|

"People say, 'Well, how did you go from foodborne disease to Luddism?' And I say, 'A lot of what I learned about Luddism, I learned from looking at food-borne disease.' I saw that these small changes that we think are so inconsequential are usually made because someone wants to make some more money to grow something faster or do something faster," Fox says. "And they can inadvertently create situations that then are a big problem, and we have to find some other technology to solve. So now everyone's saying, 'Let's irradiate meat, because we've got E-coli on it.' But no one says, 'Well, maybe we should just stop trying to make cows grow so fast.'"

On May 30 of this year, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) lifted a ban on irradiated beef in the national school lunch program, opening the way for local school districts to order meat decontaminated with gamma rays, X-rays or electrons by the beginning of next year. While it may intrigue some school children to be exposed to the same technology that in comic book lore irreparably altered Bruce Banner, thus enabling him to become the Hulk, it clearly worries others. In a letter to the Secretary of Agriculture, Sen. Patrick Leahy warned that the "scientific debate over the safety of meat irradiation is far from conclusive. It also remains uncertain how these health effects could be compounded in the bodies of developing children."

The concern about scientifically altered food extends to biotech crops. According to a recent Time magazine piece, biotech companies have launched over "300 trials of genetically engineered crops to produce everything from fruit-based hepatitis vaccines to AIDS drugs grown in tobacco leaves." Biopharming advocates put forth a number of arguments, most having to do with the relative reduction in cost. As Francois Arcand, the president of the Conference on Plant-Made Pharmaceuticals, told Time: "Molecular farming represents the pharmaceutical industry's best opportunity to strike a serious blow against such global diseases as AIDS, Alzheimer's and cancer."

The opponents of biopharming have many complaints but their main concern centers on the lax regulations biotech companies are currently subject to. According to the Washington Post, under the current FDA system, these companies are free to decide for themselves "how to test the safety of their products, submit summaries of their data—not the full data—to the FDA, and win a letter that says, in so many words, that the agency has reviewed the company's conclusion that its new products are safe and has no further questions."

Fears regarding the lack of strictures were substantiated last year when the USDA ordered the destruction of 500,000 bushels of soybeans that were mistakenly mixed in a silo of corn that was genetically engineered to fight pig diarrhea. Two-thirds of all "frankenplants," as they are called, are corn. It may be time to start growing your own.

Despite the numerous qualms, the Bush administration has pushed for the legitimization of biotech crops for use in Africa. The European Union currently opposes the extension. As a result, the Bush administration filed suit the last week of May in the World Trade Organization to overturn a ban on many gene-altered crops in European countries. "Our partners in Europe are impeding this effort," Bush said in a related speech. "They have blocked all new bio-crops because of unfounded, unscientific fears."

The suit effectively quashed secret negotiations that had been transpiring between the biotechnology industry and its opponents for over two years regarding stricter biotech regulations in this country, the Washington Post reported in its May 30 edition. While the long-term effects of this failure are unclear, it will obviously keep the status quo in place until Congress can do something about the insufficient guidelines. In the meantime, critics fear that biopharming will spread to the Midwest (right now, pharmacorn is largely grown in isolated areas of the Western U.S.) where cross-pollination will be much harder to prevent. Time reports that a coalition of 11 environmental groups is currently suing the USDA to ban the use of food crops for pharmaceutical uses and restrict the plants to greenhouses.

The battle over biopharmed crops reveals the difficult relationship a Luddite has with new technology. Biotech advocates argue that any such restrictions would irreparably delay the treating of diseases for which the crops are being mutated. Meanwhile, their opponents maintain that the potential harm, in the face of inadequate testing, is too great. When faced with technology, a Luddite is always forced to perform a cost-benefit analysis.

"The initial invention of agriculture separated us from nature in an important way, and changed the environment in an important way," Fox says. "That's not to say that we have to go back to being hunter-gatherers and live in mud huts—we just have to think about what we're doing."

Inherent in any discussion of technology is its perceived marriage to the concept of progress. But as history shows, the resulting harm, whether it is the death of "Chinamen" from laying down railroad ties in the desert heat or Native American genocide in the wake of westward expansion, is often written off as "collateral damage."

"Has there been any progress? I mean, we had such hopes for progress," Fox says. "People weren't going to be starving. There weren't going to be any wars. Everyone was going to be healthy. I saw to my shock and horror the other day that the life span in the United States is... guess where? Do you think we're first on the list, think we live longest? No, we're twenty-fifth. So, where is all this getting us? Not very far. Right now we're over [in Iraq] fighting a war that's tearing up cities and killing people. Where is the progress," she asks. "We're just doing it better. We can just destroy things a little faster."

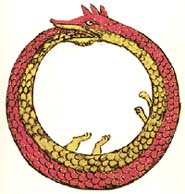

Fox's point is well taken. Any so-called technological advance is often counteracting a previous technological glitch. "If you stop to think about it," she says, "so much of what we're fixing is something that technology caused." At what point does technology resemble the Ouroboros, the classic image of a snake biting its own tail? Won't the snake ultimately swallow itself?

Fox's point is well taken. Any so-called technological advance is often counteracting a previous technological glitch. "If you stop to think about it," she says, "so much of what we're fixing is something that technology caused." At what point does technology resemble the Ouroboros, the classic image of a snake biting its own tail? Won't the snake ultimately swallow itself?

In ancient Gnostic texts, the Ouroboros also represented the eternal circle of life, or, depending on your take, the callous march of time. Like time, technology forever moves forward, and Fox realizes, as most Luddites do, this inevitability. Rather than resign herself to defeat, though, Fox continues to challenge the accepted notions that surround any sort of technological lurch.

"I think that we just don't realize how we've been shaped," she says. "Every day, there's some example to me of how unwittingly our lives are shaped by technology, whether it's filling out a form, or something simple where the machine seems to be in control." To that end, Fox hopes that her book, Against the Machine, causes readers to question the influence technology has over their lives. "I want them to be aware. So often we think it's we that are failing, that it's us," she says. "But it's that some machine out there is telling us how we have to act, or how we have to be, or how we have to adjust ourselves. And the fact that we find this a problem is not a problem. We're human beings; of course we can't be machines. Of course we can't always fit into the mechanical format."

"I think people need to ask questions," urges Fox. "They need to look at how their lives are inadvertently controlled by either a machine, or a system. Then, they need to just have the courage to take back some control over their lives, in whatever way they find most appropriate."

DISCLAIMER: THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN OLDSPEAK ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE.