OldSpeak

The Reverend Billy Wants You to Stop Shopping

By Jayson Whitehead

February 17, 2003

"Save your soul my child," a booming voice screams. "Back away from that silly little product on that shelf." The tone and mannerisms suggest a Baptist preacher from the Deep South, but the message sets it apart. "I adopt the verbal instrumentation of a fundamentalist but am saying something a fundamentalist would never say," the Reverend Billy says. "However, if they paid attention to certain aspects of Jesus of Nazareth, that’s what they would say."

***

Bill Talen was an out-of-work performance artist/playwright when he moved to New York in the mid-90s. His arrival coincided with a massive redeveloping of Times Square led by the Walt Disney Company. Gone were the sex shops, prostitutes, drug dealers, and run-down theater district. A Disney Store and a refurbished theater with a production of "The Lion King" as its centerpiece had taken their place.

|

Talen was outraged. "Being a theater person coming to Broadway, I think I’m coming to the Mecca," he says before wistfully adding. "It’s Las Vegas now, it’s gone. No one goes there and culture doesn’t happen there."

Disney’s presence paralleled the austere reign of Mayor Rudy Giuliani—elected in 1993—and his extensive efforts to "clean-up" the streets of New York. "It was very upsetting to see Giuliani’s cops picking up anybody who didn’t seem to have a credit card," Talen says. "Any person of color that didn’t look absolutely middle class, that didn’t look precisely like they would spend money in the next five minutes was swept out. And all the small vendors, the traditional characters—boom, out of there. Demonized constantly by the fake Puritanism of Rudy Giuliani."

Disney’s ascension in the wake of Giuliani’s blitzkrieg only compounded Talen’s frustration. "And here comes Michael Eisner and the kind of manifest destiny that the Disney Company enjoyed over several square blocks," he says. "They just blew away all these other businesses. I watched that happen. It was like a cleansing, if not ethnic. It was like the neighborhood got bleached."

The seeds of Talen’s anti-consumerism philosophy first sprouted at this point. "That was the nature of my theology that I developed," he says. "Don’t support this. Stop shopping. And that’s where it started—the destruction of Times Square."

***

A maverick priest named Sidney Lanier—who had started the American Place Theatre in 1963 and supported Talen’s former playhouse in San Francisco—encouraged the playwright to adopt the look and feel of a preacher to channel his frustrations through art. Raised a Calvinist, Talen initially chaffed at the idea. "I just hated the idea," he says. "I didn’t even want to spoof Christianity. I was so traumatized by my own conservative tribe—predestination and what all."

In response to Talen’s trepidation, Lanier urged him to focus on the person of Jesus and his spoken word legacy as recorded in the Gospels. "He taught me that Jesus was never a Christian. He never performed in a church or a synagogue," Talen recalls. "Jesus was some sort of revolutionary mystic, a great writer, a creator of these disturbing epigramic ironies that sort of explode in your head. ‘Let the dead bury the dead.’ You do a double take and repeat it to the person next to you and before you know it it’s a pop ditty of 2000 years ago."

|

Quite deftly, Lanier made Christ accessible for the lapsed Calvinist. "He made Jesus a person in the tradition of Richard Pryor, Lenny Bruce and the great monologists," Talen says. "And that’s what I had been producing in San Francisco. I was the traditional producer of Spalding Gray and Clair Bloom, and I had done solo shows to some degree. So he kind of pulled me out of my own trauma about Christianity."

The Rev. Billy and his Church of Stop Shopping were born sometime thereafter in an old, mostly empty Episcopal Church in Hell’s Kitchen called St. Clements that was also Lanier’s former parish. "I was the house manager," Talen says. "And I developed preaching techniques when no one was there in the middle of the night."

The church also served as a strategic location for Rev. Billy’s initial forays in consumer evangelism. "It was from there that I just walked a couple avenues to the East and started preaching in front of the Disney Store at 42nd and 7th," he says. "And then I gradually developed the idea of using retail space as performance space. I discovered how charged and dramatic it was to violate the 800 neurotic myths that fill the Disney store. You go in there and try to add a myth yourself with your own body—it’s a tremendous violation. The little neurotic Grumpy and Smiley and Aladdin and Jiminy Cricket all gang up on you and try to force you out the door. That was my first combat with American retail mythologies."

***

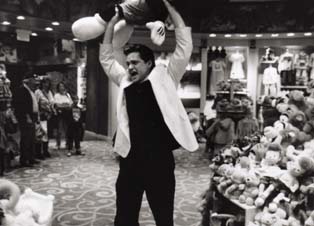

In a scene from The Gods of Times Square, a 1999 film that documents the transformation of that area of New York, the camera follows Rev. Billy as he walks toward the Disney Store, a four-foot stuffed Mickey Mouse under his arm. Once inside the store, Billy raises Mickey above his head. "People … tourists. Listen to me! Mickey Mouse is the anti-Christ," he bellows. "This is the devil. And the Disney Store is turning Manhattan into a themepark!" It’s at once very funny but also immediately apparent why such an action would be effective. Maybe too effective. Talen was arrested a handful of times for his Disney Store protests.

|

Clad in a white suit with his hair combed back in a pompadour, Rev. Billy has a striking appearance. "Elvis plus a priest’s collar, plus a tuxedo jacket," he notes. "It’s kind of a bunch of mixed metaphors. It’s part televangelist, part episcopal priest."

Then there is his animated, resounding voice. "If you just listen to preachers, they are amazing," Talen says. "As Louis Armstrong says, ‘Preachers work in the landscape between talking and singing.’ Lanier taught me to listen to a voice so that every spoken word is a note and sometimes many notes if they’re alighted on a musical scale." Talen imitates the cadence, adding a musical rhythm to his voice. "A good preacher hears the spoken word that way."

Although the Rev. Billy focused his early energies on the Disney Store, his attention soon turned to Starbucks coffee stores. The transition made perfect sense. "Starbucks comes into every neighborhood," he says. For the reverend, Starbucks was doing on corner after corner what Disney had wrought in Times Square, stripping its original culture and replacing it with a saccharine corporate substitute. An internal memo distributed by Starbucks to their New York branches documents Talen’s actions inside a store:

"Reverend Billy sits quietly at a table with devotees and then begins to chat up the customers. He works the crowd with an affirming theme but gradually turns on Starbucks. Towards the end, he's shouting. Then the Reverend's devotees hand around anti-Starbucks leaflets. After that, he heads out the door. According to a store manager, he may stand on your tables."

While the reverend has become identified with his fight against the coffee stores, he takes his form of guerrilla warfare into other chains. "I’m occasionally in Gap stores, Nike, Wal-Mart, K-Mart, McDonalds—transnational corporate outlets of that kind where you always have the same décor, always have the same product."

***

Like any preacher worth his salt, the Rev. Billy has a dedicated congregation that he teaches how to walk the righteous path—albeit one of anti-consumerism. "We have a choir, we have a band, we have deacons," says Talen. "We have people that rise out of the congregation and have some serious flashes and pull their credit cards out of their wallets and fess up. There’s a feeling of release." But any comparison to a normal church service ends there. "We have a sort of post-religion spirituality," he says. "But we never use the word religion, we never use the word spirituality. All those words we consider to be products in themselves. They are all bankrupt. They are all used by people we don’t want to emulate. Something does happen at a Church of Stop Shopping service when it really gets rip-roaring. And whatever happens it’s a good thing. It’s attached to good values and it’s also just physically and psychically a pleasure."

When he is not torturing corporate entities or preaching to his followers, Talen is a college professor. He teaches a class at New York University called Street Performance in the Mediated Age: The Artist as Citizen. "I have great students, really brave" he boasts. "I couldn’t come to class because they were occupying Hillary Clinton’s office after she voted for the war." He is also putting the finishing touches on a book to be published by the New Press, "What Should I Do if Reverend Billy’s in My Store?" The title is taken from the Starbucks memo.

I recently spoke with Bill Talen by phone about his alter ego, the Rev. Billy’s participation in anti-war protests, his link to Christianity, and whether he ever feels the urge to shop.

oldSpeak: Aren’t many of the stores that you target for performances symbols of America on a global level?

BT: They symbolize the recent economy. All their products are made in sweatshop settings. They multiply by fancy financing and destroy neighborhoods. They come in and destroy the thing that people have between them. The culture making that we ourselves do is inhibited and replaced by their attempts to surround us with an atmosphere that impacts us not just at the point of a product’s answer to your needs in a service sense but they also try to engage the personalities of the consumer. And in engaging the personality of the consumer they do not have a conversation with the consumer that will leave alternatives for the consumer outside of consuming. In the Church of Stop Shopping, we believe that ultimately a kind of dull emptiness takes over as your life becomes supervised by the all-consuming retail environments that are the new American consumerism.

Why do you take the Rev. Billy to anti-war protests?

|

A year ago after 9-11, anti-consumerism became the peace movement. If my best known focus became the resistance to the second biggest import in the country—coffee—the biggest import of course is oil. There’s no difference at all. Nothing that I do isn’t completely driven by cars. The automobile has had a huge impact on New York City neighborhoods. Certainly the suburbs and rural areas have been decimated by the number of cars and the degree to which architecture, highway design, and town design is determined by this bubble of glass and metal that makes it possible to really not deal with each other. There again the possibility that we might have a conversation that we originate ourselves is replaced by the sheeny surface of the automobile. We don’t get to be with each other in public space. There’s this remarkable tradition of zoning people and city designers just constantly deferring to the hopes that people can drive cars through their towns as fast as possible. And they’ll capture them outside of town in a mall or if they capture them inside of town it’s also in a mall now. Main streets are replaced by malls. Malls are obviously designed for cars. The idea of parking and walking into public space has been replaced by parking on private property and walking into private property.

I’m really a champion of people being left to create culture in public space. Tell jokes, tell gossip, tell stories, shove each other around, paint each other, meet in groups of three or more, invent language, shout, gesture, run around. If you do what I just described in certain places in New York City or certainly in a mall, even on something that might be called a public sidewalk, you bring the attention of the police. We’re in an intensely puritanical phase of our culture right now. The retail behavior systems are so narrow and yet of course they’re represented in advertising as being freedom itself. It’s an interesting contradiction.

In the wake of 9-11, the consumer was identified with the concept of a patriot.

What you’re saying is absolutely true. The wars that we seem to support habitually are so much now products. They’re products you purchase. They are video games, they are media, they are magazines, they are TV shows. We refuse to believe that there’s any violent consequences of these wars. We believe that they’re good products, that they drive the economy. They are profit centers. Why has the commercial media been so pro-war? Why do they ignore the huge marches? The peace movement has already recorded in numbers record-breaking crowds and they continually are described by the commercial press as splinter groups. They are consciously censored and marginalized again and again and again. You’ve got huge groups of people in Florence, England, Washington, D.C. Many, many people are upset and they are trying to make their presence known and the media really doesn’t carry it.

|

The media really is censorious. They are instructed that they have a profit center that they must regard. Walter Isaacson from CNN tells his people, "We don’t want to see blood. We don’t want the consequences of what wars do to come back to the United States." In Europe, of course, they show the bodies, they show the consequences.

So war is a product. Somebody who is resisting consumerism and doesn’t like it that his neighborhood has become a sort of hushed silent mall with people hurrying to get out of the way of the cars and never talk to each other anymore—that is upsetting. But a consequence of our consumerism is that we have a violent foreign policy. We must finance cars with gas and oil that’s cheap. The quid pro quo is so direct between the design of our towns for cars and the need to colonize a place like Iraq sitting on forty percent of the world’s crude or Venezuela. To cook up trouble in places where we are dependent on that energy. And to have so many of the senior officials in the administration big oil executives—Cheney getting 17 million bucks from that last tax break—c’mon, this is not democracy. It’s straight payoff.

Does it surprise you that churches don’t speak out more against consumerism?

If I can just generalize, a lot of churches and synagogues are people dressing up and being their class, their tribe. Even the black sanctified and gospel churches, you see that a lot. Let’s dress up and be proper. It’s a way of ascending in the American tradition, ascending up to another class. There was a point where Billy Graham was no longer middle class. He was becoming rich. He wore nicer clothing. And certainly we’ve seen that happen with the Jimmys and Jerrys and Billys. There’s a certain point where they become successful and when we see them on TV they have nicer clothing and they have bigger churches. Reverend Schuller and the Crystal Cathedral, he’s got some California real estate there. They don’t talk about Jesus throwing the moneychangers out of the temple all that much.

Because you have been a performance artist for quite a while, and you teach it in a course, there’s a way one could look at what you’re doing and be cynical about it … one could wonder how much of what you do is strictly performance art, and how much is sincerely out of conviction.

I think it’s not so much from being from the tradition of being a playwright and an actor, because hopefully that isn’t thought of as a world of disingenuousness. But I think for some people, they wonder about my sincerity because it’s parodic, because it looks like it’s got that vibe to it, at first blush. Saturday Night Live has been so boring for so long because they never have a point of view, they don’t believe in anything. They’re stuck in this mid-level of making derogatory comments about people, but they don’t take any point of view because they can’t, because they’re commercial. So therefore they can only go so far. They have a problem with celebrities now. Celebrities can’t really have a point of view. Bruce Springsteen’s Rising album is sentimental, but it doesn’t really have a point of view about 9-11. You really have to come out, and you really have to say, "Let’s not bomb those people."

|

The people in the towers at 9-11, the last things they said into the phone, a lot of them were saying, "I love you. Tell the children I love them. And I will see you again." There was a kind of magic; they had lessons to teach us. There are 157 conversations that have been transcribed, and many of them have that sort of talk. How that got turned into violence against other people, who will now be put in the very same position by our returning fire … that means those people have been misrepresented by people who call themselves "representatives." And it’s the people at those endless memorial, uniformed salutes, pet eagles flying over, F-111’s flying over, video games … there’s something to say about 9-11 that is clear. So commercial people haven’t been able to talk about it, because it really is about opposing commercialism. And it’s been swept away in the land of American products. The land of American products does kill people.

I mentioned you to a Christian associate, and he asked if you were mocking the kind of preacher that you’re imitating. Is there any satire in what you’re doing that is aimed at preachers in general?

Well, they’re sort of the cultural nemesis of the average artist in this country. If there’s one type of person you would want to attack, it would be the money-grubbing false healers of late night television. But now they’re 24-hour television—what am I saying? Have you ever watched the Trinity Broadcast thing? It’s almost like professional wrestling, really.

I would say that your Christian friend is right; that’s one of the elements. But it only happens in the first couple minutes of a performance. After that, something else starts happening. It’s only a way of making a community. We shout "Hallelujah!" together, and it’s funny for a moment, but then you’re on a journey after that, toward trying to solve something about a local community garden or trying to protect a person who’s had an independent business on the corner for thirty years, and they’re getting run out of town by NASDAQ funny-money from some chain store. And when we pray, it becomes prayer. Do I want to use the word "prayer"? No. But we address the god/goddess/mystery thing. That’s the latest thing we call it, the god/goddess/mystery thing. And you don’t do that from a position of parody. So "Reverend Billy" is a just a way to meet and greet. The parody’s over in seconds.

Do you have any shopping guilty pleasures?

|

That’s a good question. One of my directors, Tony, wanted to have a person run in the center of one of the Church of Stop Shopping services, stop everything and put a projector on the stage and start showing pictures of me huddling with London Fog raincoats, trying to cover up a $5 Starbucks latte, sticking my hand up, trying to cover my face. I think it’s a great idea. And if I could get into my method acting, I could be on my knees sobbing like Jimmy Swaggart was when his wife was in the first row, "I have sinned." Can you imagine? It would be so much fun.

I am in fact impacted heavily by advertising in a way that really upsets me. I have an obsessive and leisured relationship to the nine thousand advertising events the average New Yorker gets hit with every day. I actually do have trouble shopping. It turns out I have trouble even getting the necessities. I had to get a new suitcase. And getting used luggage is a little… you know, my people go to thrift stores, we get out of the economy and we find a way to barter, and we find a way to start new economies. A gift economy is the model. But you want to get a suitcase. So you say, I got a hundred bucks here, and I’m going to get a suitcase. And I couldn’t do it. I really tried. I did it with my wife… it was very difficult to do; I couldn’t put the money down. It turns out that it’s actually true. If you shout "stop shopping!" all day long, words make a difference, words are real. So I ended up just going back to my beat up, old suitcase.

DISCLAIMER: THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN OLDSPEAK ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE.