OldSpeak

The Beatles in Hamburg: An Interview with Ian Inglis

By John W. Whitehead

January 8, 2013

The most successful and influential pop group of all time, the Beatles landed in America in February 1964. By the time the Sixties came to an end, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr had taken the world by storm, not only becoming icons of popular culture, but also collectively creating an unprecedented legacy of hit singles and best-selling albums. It’s particularly telling that when Rolling Stone recently chose the top 500 albums of all time, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was perched at the top, with Revolver, Rubber Soul and The White Album following close behind in the top ten.

Yet none of the Beatles’ amazing success happened overnight. Indeed, long before the Beatles stunned the world with their musical prowess and charm, they cut their teeth, so to speak, in the most unlikely of places—Hamburg, Germany.

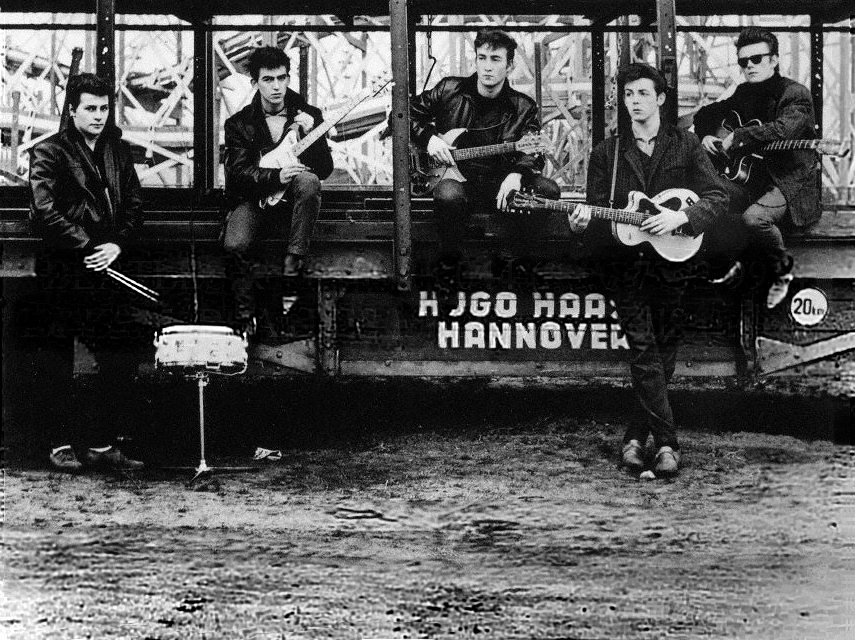

As inexperienced musicians, still in their teens, the Beatles made their first appearance onstage in Hamburg in 1960. Over the next two years, the Beatles would play four to five shows a night—all the while honing not only their musicianship but their songwriting skills, as well.

As Ian Inglis reveals in his insightful book The Beatles in Hamburg, the Beatles’ Hamburg experience was to play a decisive role in their remarkable careers. Facing rowdy bar crowds, shifting and unpredictable audiences and demanding work schedules, not to mention the arrival and departure of key members of the group, the Beatles learned the art of performance. This, along with their budding musical talent and proficiency as artists, elevated the Beatles above and beyond their competitors. Hamburg, Germany, then, can aptly be described as the birthplace of the Beatles, as Inglis makes clear in The Beatles in Hamburg.

Inglis was born and grew up in Leek, a small town some seventy miles from Liverpool. His summer holidays were often spent in some of the popular seaside resorts near Merseyside: Southport, Blackpool, Rhyl, and New Brighton. In 1963, his parents took him to see the Beatles on stage at the Odeon Cinema in Llandudno in the same week that “She Loves You” was released in the UK. After leaving school, he worked as a journalist in Stoke-on Trent, before deciding to study Sociology at the University of London. Three years undergraduate study was followed by a postgraduate degree in Mass Communications at Leicester University. Since then, apart from a spell with BBC local radio, he has taught at Leicester and Northumbria Universities. He gained his PhD in 2003, and has been researching and writing about popular music – particularly the music and career of the Beatles – for twenty years. Among the books to his credit are The Words and Music Of George Harrison and The Beatles (Icons of Popular Music). His favorite Beatles single: “She Loves You.” His favorite album: Rubber Soul. His favorite Beatle: “Whichever one I’ve just been thinking about.”

Professor Inglis took a few moments out of his busy schedule to chat with me about his new book.

John W. Whitehead: From your book and what the Beatles have said, it seems like Hamburg was a transforming time for what we knew as the early Beatles. Can you explain?

Ian Inglis: Yes, I think it is important to remember that, when the Beatles originally went to Hamburg, what was it, the summer of 1960 they couldn’t be described as a band or as a group in any real sense. There were only 3 of them. They didn’t have a drummer. They only played very intermittent occasional gigs, a dance here, a pub here, a social hall there. Often they would go for weeks without performing, without playing at all. They rarely rehearsed. They didn’t see an awful lot of each other. They lived at home. It wasn’t as if they were out on the road touring together and spending a lot of time together. So really, they were really just a collection of four or five young lads, four or five teenagers who had vague ambitions about being successful musically but nothing more than that.

JW: There were three primary Beatles—Lennon, Harrison, McCartney. However, Sutcliffe and Pete Best were in the band as well.

II: Yes, that’s right, and remember Sutcliffe was not a musician. He himself admitted that he was astonished when he was asked to join the Beatles. So he brought nothing musically to the group, and Pete Best was recruited literally just a couple of days before the group went to Hamburg. Thus, they were very untried and amateur. They weren’t making a living from music; it was a hobby for them. They were semiprofessional at best and really best described as amateur musicians. However, if you fast forward 2 years to the time of their final gig in Hamburg in December 1962 and look at what had happened to them in the meantime, they had just released “Love Me Do,” it is to go into the British charts. They were about to go on a short tour of Scotland at the beginning 1963, but no one had even the remotest idea of how successful they were going to be in the next few months. So, by the end of 1963, they had four #1 singles, two #1 albums, Beatlemania was sweeping the country, and it is that sort of transition. Indeed it was a very dramatic transformation between what they were like when they first got to Hamburg and what they were poised to achieve when they left Hamburg for the final time. A lot of the information we have about Hamburg in this country has come to us mainly through various movies, such as Backbeat, all of which tell very sensationalized stereotyped stories along the lines of sex and drugs and rock and roll, of which I am sure there was plenty, but I thought it was more important to try and look at what happened more objectively. For example, what actually was it about Hamburg at that time that allowed this transformation to take place? So that was what I originally intended to do.

JW: One of the key topics you point out in your book is that the Beatles spent an estimated 800 hours and over 273 nights playing in Hamburg. That was before the Cavern. Thus, it was in Hamburg that the Beatles learned to be a band. They learned songs. They were having to hone and build up their talents. So obviously Hamburg would have to be essential in Beatle history.

II: It is absolutely crucial. You are right. The number of hours they spent on stage in Hamburg is greater than the amount of time they spent on stage in the Cavern. They made roughly the same number of appearances, but at the Cavern they would typically be on for an hour set at lunch time or hour and half in the evening. In Hamburg they were playing at least four hours every night and six hours on the weekend. Thus in terms of sheer hours, they put far more work in the clubs of Hamburg than they did in the Cavern. Of course, as you know, their first gig at the Cavern wasn’t until February 1961, which was after they came back from their initial three month spell in Hamburg, and it was largely as a result of the way they musically tightened up in that short period of time. Thus when they came back to Liverpool, they immediately impressed audiences with a number of iconic gigs and concerts they did just after coming back from Hamburg. It was that that secured them their first date in the Cavern. So it is possible to argue that, without the Hamburg experience, they would probably have not been offered any appearances in the Cavern at all. Therefore, Hamburg set the foundation, if you like, for almost everything that followed.

JW: You discuss the Beatles and drugs in Hamburg. Astrid Kirchherr downplays the drug factor. Do you think the drug factor had anything to do with their development or was the possible use of drugs something that kept them awake so they could play?

II: I think the drugs they took in Hamburg just kept them awake so they could play. Preludin, the drug they mainly used, was an over-the-counter pill that was easily available in Germany. It was less easily available in Britain and was used as a stimulant. I think later on, certainly after they started taking LSD, you can look at the way in which acid inflected lyrics started to permeate a lot of their songs from 1965 onwards, but I think in the early days in ‘60, ‘61 and ‘62, Preludins were taken simply to keep them going. In Liverpool they had been used to playing half an hour or an hour ever so often. In Hamburg, they were doing numerous hours every single night, and without Preludin they would have been literally exhausted and not able to carry on. A lot of other musicians in Hamburg experienced the same thing. Drugs were simply a way of giving the Beatles additional energy to complete four or five hours a night on stage.

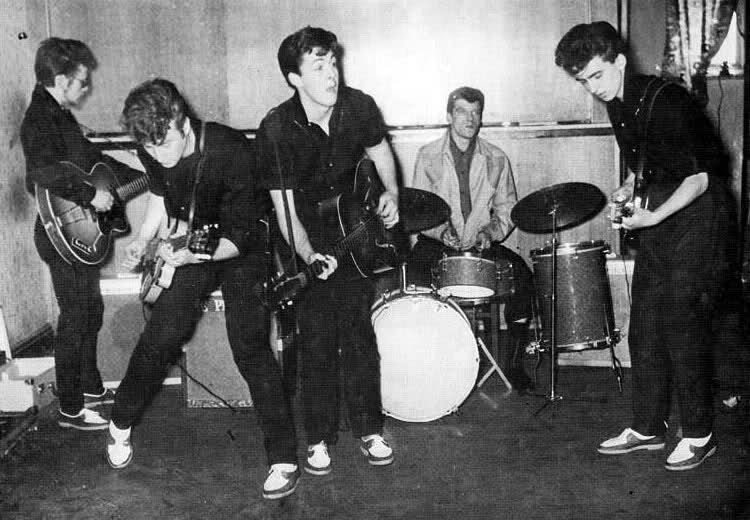

JW: Audiences were quite different in Hamburg then, let’s say, they would have been in New York or Liverpool. In Hamburg there were drunks in the audience. Lennon fought with members of the audience. As you show in your book, Lennon used profanity and cussed at the people in the audience. Isn’t it true that Hamburg was where the Beatles learned to perform, or in other words, to make show?

II: I think it was. In Liverpool at the Cavern their gigs were fairly predictable, and by that I mean the audience tended to be the same customers over and over again coming back to see them. They had their local fans in Liverpool who would treat them with a certain amount of affection; many of the audience members were friends with the Beatles. The audience members were the same sort of age. So it was a very local, a very sort of stable scene. In Hamburg, it was completely different.

JW: There is a picture of John Lennon with a toilet seat around his neck in Hamburg performing on stage.

II: Yeah, that’s right. In Hamburg the audiences were different every night. There were people who were in The Reeperbahn for the sex trades, the brothels, the clubs, the bars, and the strip clubs. They were not just attracted to the music. They were there not because they liked the music particularly or because they wanted to see the Beatles but simply because it was an added incentive. That is why Bruno Koschmider and the other club owners wanted the Beatles and groups like that. They weren’t particularly interested in their music, but they did think they might be a useful device to entice in additional customers. So the Beatles had more of a fight on their hands to entertain audience members who weren’t there to listen to their music. The Beatles had to really pull out all the stops in order to maintain some sort of audience interest, and that is why I think they learned this kind of rowdy interruption, this yelling and screaming and shouting and running around and jumping off the stage. This was the “mach schau, mach schau” which Koschmider said enhanced their act. It made it something more memorable. This was so the customers would be more likely to come back to that club than to go on to somewhere else, and that is exactly what the club owners wanted. They didn’t want polished professional singers by any means; they wanted entertainers who could provide some sort of excitement.

JW: It was so people would buy drinks.

II: Exactly. That is what the Beatles learned they had to do. They had to function as entertainers to entice people into the club and once they were there, to keep them there. Their sort of onstage antics were a part of that.

JW: Supposedly one of John Lennon’s friends brought him a video of the Sex Pistols on stage singing. Lennon looked at it briefly and said “Ah, we did all that in Hamburg.” Were the Beatles the first punks?

JW: Supposedly one of John Lennon’s friends brought him a video of the Sex Pistols on stage singing. Lennon looked at it briefly and said “Ah, we did all that in Hamburg.” Were the Beatles the first punks?

II: I think had the Beatles come along 14 or 15 years later they would have been described as punks -- especially in the way they dressed and the music they played. It was loud, basic three-chord guitars with no fancy instruments on stage. Just three guitars and drums which is famously what a lot of the punk groups in the UK used in the mid ‘70s. It was loud aggressive rock and roll. That is what the audiences wanted. Fifteen years later, that would have been called punk music certainly. Thus, you could say that the Beatles were the first punks. Although, I suppose you could go back to the 1950s and say that Gene Vincent was the first punk. I think that is one of the interesting things about this sort of popular music -- how it repeats and recycles itself, and certainly the Beatles in Hamburg were recycling other people’s music. For a long time they played very few of their own compositions and simply repeated the sort of music that had inspired them in the mid ‘50s. So, from Gene Vincent and Jerry Lee Lewis in the mid ‘50s, to the Beatles and the Stones in the mid ‘60s, to the Sex Pistols and others in the mid ‘70s, you can see this sort of constant recycling of ideas and themes and styles of delivery.

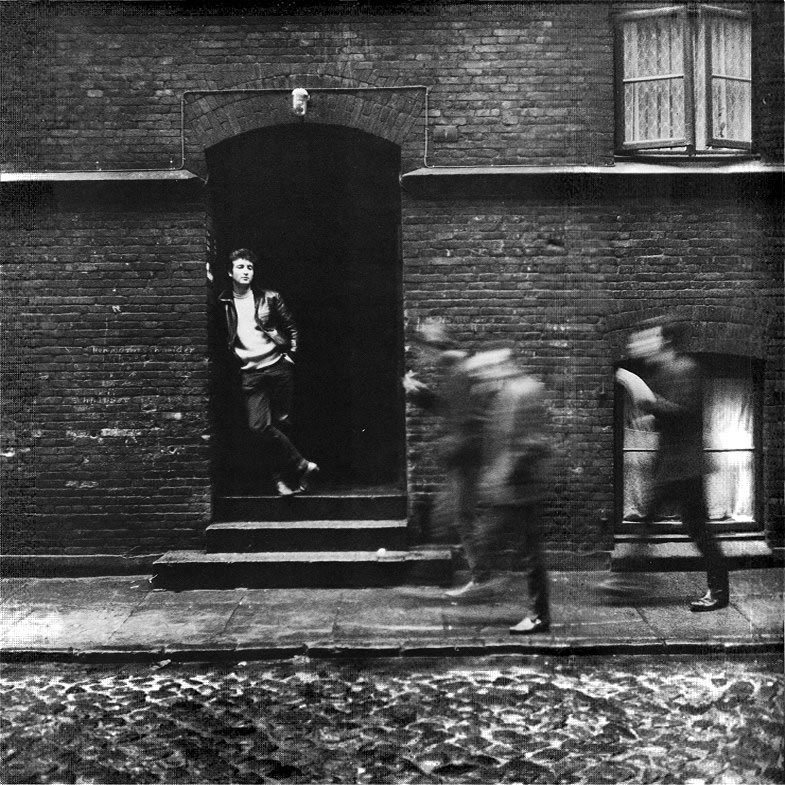

JW: Tony Sheridan, as you reveal in your book, was a great influence on the Beatles. John Lennon’s wide legged stance was probably copied after Tony Sheridan. Then you have Jürgen Vollmer, Klaus Voorman, Astrid Kirchherr, who also had what might be called an avant-garde influence on the Beatles.

II: That was one of the interesting things about the Beatles in Hamburg. They were in a rough, working class, red light district of Hamburg, and yet they managed to make friends with some very creative artistic middle class intellectuals like Vollmer, Kirchherr and Klaus Voorman. That undoubtedly gave them an insight into other ideas about fashion, about music, about literature, about image, about creativity, about presentation and so on. I think it has been said that if the Beatles met people like that back in Britain, back in Liverpool, they would have dismissed them as being pretentious arty types. However, when the Beatles met them in Hamburg, they were quick to welcome them as glamorous, exciting, bohemian individuals, and of course, the influence was reciprocal. Kirchherr and Vollmer and Voorman and others welcomed the sort of earthy rock and roll and raw entertainment that the Beatles gave them, so the two fit together quite well I think. One was attracted sort of by the arty image of the bohemian world, and the Germans were attracted by the sort of raw excitement of rock and roll. So the two fit together very nicely, and the importance of Sheridan, I think, can’t be overstated. He was an absolutely crucial figure not just for the Beatles but for a lot of the acts that came over to Hamburg in the early ‘60s.

JW: The Beatles first recording was backing Tony Sheridan.

II: That’s right. In Hamburg, Sheridan recruited the Beatles to act as his backing group. They recorded several songs during a two or three day session, and the Beatles managed to record a couple of numbers by themselves, “My Bonnie” and “Ain’t She Sweet,” but Sheridan’s influence was enormous not only in terms of his musical repertoire. He also introduced the Beatles and other groups to a whole lot of obscure rock and roll and R&B tracks that they might not have come across before. Sheridan influenced the Beatles in a style of musicianship, with legs apart and that high chested style of delivery and style of guitar playing. It was used by Lennon and Gerry of Gerry and the Pacemakers. They all adopted that kind of stance. So again the Beatles incorporated what they saw by Sheridan and by others into their stage craft, and it became a distinctive part of who they were.

JW: When the Beatles hit America, it was the hairdo that was the first thing you noticed. Everybody at the time had crew cuts, and as you argue in your book, Jürgen Vollmer was the person who actually gave them the haircut.

II: My research shows that Astrid Kirchherr persuaded Stuart Sutcliffe to comb his hair forward and the other Beatles didn’t really want to go along with that. They thought it was rather effeminate, rather peculiar, but gradually they came to like the idea of that hair style. During a visit to Paris to visit Jürgen Vollmer, who had moved there to work as a photographer, he persuaded John and Paul to let him cut their hair and comb it forward in the same way. Once they had done that, George Harrison followed suit, and that became such an integral part of their image. They became the four mop tops with long hair. When we look at it now it doesn’t seem particularly long. It is also interesting that only Pete Best refused to comb his hair in that way. I think that was a small but significant indication of the kind of division between him and the rest of the Beatles. Best didn’t go along with a lot of the things that the others wanted. So in lots of small ways I think there was a distance between Best and the other Beatles right from the start in Hamburg.

JW: It was in Hamburg that the Beatles met Ringo, and Ringo was a key component to the future of the Beatles.

II: Oh, absolutely. The Beatles would have not been the Beatles without Ringo. That’s right, they met him in Hamburg. Actually, he had been a drummer in Liverpool, but I don’t think they had come across him before. They met him when they shared the bill with Rory Storm and the Hurricanes.

JW: John Lennon, to paraphrase him, said something to the effect that “Ringo was famous before we knew him.”

II: Rory Storm and the Hurricanes were, in many ways, Liverpool’s leading group. They were flamboyant and very exciting personalities on the stage. Rory Storm in particular was seen as a real showman. I believe he was known in Liverpool as “Mr. Showman” or “Mr. Showmanship,” and Ringo was a very important part of that group. Ringo had his own little spell on stage called “Starr-time” when he would take the vocal mike and perform two or three numbers each night by himself. He was quite a star within what was Liverpool’s leading group. When the Beatles met him and began to spend time with him when they were in Hamburg at the same time, they warmed to each other very quickly. They all had the same sense of humor. They liked to hang out together and gradually Ringo began to spend more and more time with the Beatles. So it was probably inevitable that at some point he would have been asked to join the group. Ringo did jam with the Beatles and record with them on a couple of occasions in Hamburg. Thus, although it might have been a shock to outsiders when Pete Best was fired from the group, to many people in Liverpool I think it made sense. They knew that Ringo had played with the Beatles. They knew that Ringo and the Beatles got on very well, and it just seemed a kind of logical step.

JW: There is another key element about Hamburg. Because the Beatles were on stage so much, it forced them to not only write original music but also to do all of those great covers. When you hear some of the Beatles cover songs, then you hear the originals, it’s as if the Beatles stole the songs. They were so good at taking other people’s music and, as John Lennon said, “Making it better.” All of this happened in Hamburg.

II: That’s right. The Beatles had to do covers because they were expected to play for such long periods of time each night. They didn’t have a repertoire when they got to Hamburg that would allow them to do that without simply repeating what they had already done. So it was pretty important that they get hold of as much new material as they could. Part of that involved writing their own songs, but they were very, very self-conscious about that. They didn’t really think their songs at that stage were very good. They probably included one or two in their nightly shows, but throughout their period in Hamburg, they remained a covers band, and you are right, many of the covers they performed are probably better known now through the Beatles versions than they are in their original versions. For example, “Twist and Shout” is always associated with the Beatles, and there are probably very few people who realize that it was originally performed by The Top Notes. You could say the same thing about a large number of their songs. They took the songs and made them their own.

JW: Bill Harry, the Beatles biographer and historian, said “Hamburg’s importance has been exaggerated by nearly every author, Liverpool is far more important.” Harry said “the groups loved Hamburg only because they could get booze 24 hours a day.” Is Bill Harry trying to protect Liverpool? Any study of history shows how important Hamburg was to the development of the Beatles.

II: A lot of the people in Liverpool have a vested interest in claiming the Beatles as their own and in trying to hang on to the Beatles. Clearly, Liverpool was very important. The Beatles came from Liverpool. They were either born or grew up in Liverpool. They met each other in Liverpool, and they played a lot of dates and places in Liverpool like the Casbah and the Cavern. Thus, clearly Liverpool does play an enormous part in the Beatles story, but in terms of the Beatles actually developing as a performing group and learning the craft of performance, it was what happened in Hamburg that was the crucial factor. In Liverpool they were playing half hour or one hour long sets, and they were perfectly able to do that without any problems. They had an ample repertoire of songs. They knew where their audiences were. There was little in the way of surprise or unfamiliar expectations for them. It was only when they got to Hamburg and found what they had to do, that they realized that they would have to sit down and change their act, bring more music into their act, develop their songwriting ambitions and bring changes into their stagecraft. While they were in Hamburg, they acquired new instruments and they began to dress in different ways. They combed their hair forward, and they met a whole gang of different people who they would have never come across back home in Liverpool, and indeed, all the Beatles themselves say quite categorically that it was Hamburg that really switched them from being decent local musicians in Liverpool to being outstanding stage musicians when they came back from Hamburg. Lennon, Harrison, and McCartney all say that, as well as other musicians. Gerry and the Pacemakers, members of The Swinging Blue Jeans, the Searchers, King Size Taylor, and the Dominoes all make the same point that it was Hamburg that really forced them, in a way, to make that transformation. Thus, although Liverpool is clearly massively important as the home of the Beatles, it is Hamburg that is more important as the place which nurtured and transformed the Beatles from being a local semiprofessional group into the very aggressive, polished, competent outfit they were when they came back from Hamburg.

JW: The worldwide fame of the Beatles was the Ed Sullivan Show appearance in February 1964. I remember watching that performance. They performed live to some 80 million people in the United States on television. They were really accomplished performers. That was the first thing that sold you. The second was they could sing and write. Allan Williams, to quote from your book, said “When the Beatles came on, it was as though someone had pressed ever so gently on the nervous system of each and every boy in the hall.” Astrid Kirchherr said they were like “human magnets.” Brian Epstein said he had never seen anything like the Beatles on stage. Again, all that was learned in Hamburg. However, did the Beatles have some other quality or qualities that helped them over and above the other groups that went to Hamburg?

II: Yes, they did. First, the performance aspect is very, very important, and it is important to stress that. At the time in Britain, there were very few groups. There were lots of solo singers, people like Cliff Richard and Adam Faith, Billy Fury, Craig Douglas, and girl singers like Helen Shapiro and Petula Clark and so on. They were very clean cut, very proper, very sensible, very polite, very conventional sorts of musicians and performers who, to a greater extent, simply copied people in the states like Elvis, Pat Boone, Buddy Holly, and so on. So, British popular music was in a rather complacent condition in the early ‘60s. The Beatles as a group were immediately different from that. There were four of them rather than just one. There were three singers rather than just one lead singer and a backing group. They wrote their own material, which was virtually unheard of, and they had such a wide repertoire. They also had developed crucially in Hamburg, and I don’t know whether you would call it a sense of humor, but they developed a ready sort of wit and a kind of spontaneous approach. You can see this in their press conferences.

JW: The Beatles were very good with the media.

II: That’s right, they knew exactly what to say, and they were very light hearted and flippant, and they were very quick and smart and charming and so on. Part of that too was learned in Hamburg. This idea of how to handle people, how to respond to people, how to handle an audience, whether it’s an audience in a club or an audience of journalists. Ultimately, of course, their success is grounded in their music and, in particular, in the songs that they themselves wrote, but it is more than that. It has to do with the sort of difference that they emphasize between themselves and other British popular musicians. It has to do with the fact that they rarely turned down a radio slot or a TV appearance. It has to do with the fact that they allowed Brian Epstein to direct their career along particular roots, although they didn’t particularly want to dress in suits and all that.

JW: John Lennon said they sold out when they put on suits.

II: Lennon said that afterwards. However, Epstein was shrewd enough to realize: “Look lads, if you want to get a foot in the door, you’ve got to play the game. You have to do what is expected of you. You have to play the game. Go along with it because if you don’t go along with it, you are never going to get a shot at being successful.” The Beatles were shrewd enough to realize that he was right. They did have to play the game. They did have to put on suits and ties. They did have to stop jumping around, swearing, eating and smoking on stage. So you could call that selling out if you like, but on the other hand, you could simply call it common sense. If they merely wanted to stay playing in clubs, they didn’t need to change at all, but if they wanted to become successful performers who people would invite onto TV and on to radio and to do interviews and to take photographs of and so on, then they had to change along the lines that Epstein outlined. Looking back, Lennon was very critical of them, but I think at the time he and the other Beatles were reasonably happy to go along with it. Remember they had been together in some form or another since 1957, and after five years, they hadn’t really achieved a lot apart from local fame in Liverpool and then in Hamburg. Thus, they didn’t have a lot to show for those five years together. They hadn’t even had a recording contract until 1962. When Epstein suggested that they should smarten up their act in particular ways, they couldn’t think of a good argument why they shouldn’t. It seemed like this made good sense at the time. Their success in Britain and ultimately around the world was a combination of a number of factors: The fact they were a group rather than one person, that they wrote some pretty outstanding music, that they had three vocalists rather than just one, that they combined cover versions with their own compositions, that they had a certain sort of infectious charm which set them apart from other popular musicians and the very complacent state of British popular music at the time. British popular music was in the doldrums. It was going nowhere. There was no ambition. There was no drive. It was a very weak, insipid rather middle of the road imitation of American styles. Put all that together, and the Beatles came along at exactly the right time and did exactly what was required of them to become successful.

JW: The Beatles music and influence is virtually everywhere today. Why do you think the Beatles had staying power while other groups didn’t?

II: I suppose it is because they were actually better and their music was better. One of the things that enables the Beatles to be as relevant today as they were 50 years ago is that they, more than any other group, are associated with the 1960s, and the 1960s, certainly in this country, and I am not sure in the states, but certainly over here in Britain, the 1960s are still seen as the century’s most beguiling, fascinating, and exciting decade.

JW: It is seen as that also in America.

II: The Beatles, because they were the first group, the first popular musicians to really spearhead that new direction for popular music in the 1960s, will always be associated with that decade. Thus, whenever there is a kind of nostalgic retrospective analysis of the 1960s, the first thing, the very first thing, that comes up is the Beatles and their role in those cultural shifts and cultural transformations in the 1960s. They are popular musicians, but also, they have become, if you like, a historical event in themselves rather like the Kennedy Assassination, rather like the landing on the moon. The Beatles have become a part of history in a way that other popular musicians haven’t, and that helps to establish them as being known and relevant and recognized today, but ultimately it comes back to the music. Their songs are outstanding pieces of music today just as they were 40 or 50 years ago, and the fact that you can play the first few bars of “A Hard Days Night” or “She Loves You” or “Please Please Me,” and kids who were just born within the last 15 or 20 years will immediately recognize what it is and know who the Beatles are, says something, I think, very important about the staying power of their music.

DISCLAIMER: THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN OLDSPEAK

ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE.