OldSpeak

Reverence for the Union Jack

By Jayson Whitehead

February 13, 2006

With yet one more attempt to restrict flag burning stumbling before the Senate this past summer and the threat of another effort always looming, we take a look back at and talk to the defendant in the 1989 Supreme Court case, Texas v. Johnson.

With yet one more attempt to restrict flag burning stumbling before the Senate this past summer and the threat of another effort always looming, we take a look back at and talk to the defendant in the 1989 Supreme Court case, Texas v. Johnson.

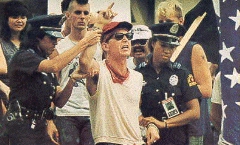

On a summer afternoon in 1984, Gregory Johnson, the 28-year-old spokesperson for the Revolutionary Communist Youth Brigade, made his way through a throng of protesters and then stopped across the street from Dallas City Hall and set fire to a United States flag.

Inside the building, the Republican National Convention—celebrating the renomination of Ronald Reagan—was in a fevered pitch, filled with thousands of jubilant supporters lost in the red, white and blue flags, bunting, and assorted patriotic paraphernalia.

Outside, city police were poised for such an act of defiance and quickly broke up the irreverent challenge, carting Johnson and nearly a hundred of his peers off to jail. Out on bail hours later, the obstreperous Marxist was hardly free. Charged with violating Texas’s “Desecration of a Venerated Object” statute, he faced up to a year in jail and a $2,000 fine.

At the district court level, Johnson was predictably convicted of violating the statute. Allies such as his attorney, the renowned William Kunstler, and David Cole from the Center for Constitutional Rights were proving to be of little help. After the Court of Appeals upheld the conviction, a year in a Texas cell looked increasingly certain.

From the beginning, Johnson and his defenders had argued that his immolation of the flag was meant as a social and political commentary on the man being honored inside Dallas City Hall. Johnson, to this day, maintains such motivation. “This was Reagan who had backed death squads in Central American countries like El Salvador, Nicaragua, Honduras and Guatemala,” he recently explained over the phone. “Tens of thousands of people had died there at the hands of these death squads. He had bragged about supporting the Contra mercenaries in Nicaragua who were trying to overthrow the Sandinista government. He was belligerent about nuclear war with the Soviet Union, made jokes about ‘I’m pleased to announce I’ve signed legislation that has outlawed the Soviet Union. We begin bombing in five minutes.’ He had invaded Grenada. This was Reagan,” he reiterates emphatically.

The day of his arrest had begun with an hours-long march through the streets of Dallas and past many of its largest corporations, where one protester grabbed a flag girding one of the buildings. By the time the marchers had reached their final resting place, nerves were shot and bodies were dehydrated. The small group was unified in its disgust. “Reagan, Mondale, which will it be? Either one means World War III,” rang the chant. “Red, white and blue, we spit on you,” the crowd alternately shouted. “You stand for plunder, you will go under.” As the demonstration reached its pinnacle, one of Johnson’s peers handed him the Stars and Stripes. At that point, standing across from a building draped in red, white and blue, lighting it seemed like the only thing to do. “On one level, I think it was a natural culmination of the protest,” Johnson recalls.

The defendant’s motivations were inconsequential to Texas authorities. The statute had been passed precisely to prevent and punish this exact sort of action. Yet, despite their early victories, the attorney general’s office had to be concerned. Since West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette (1943), the U.S. Supreme Court had regularly carved out First Amendment exceptions to a mandated allegiance to the flag. While the Court had specifically dodged the constitutionality of a law such as Texas’ that criminally sanctioned such desecration, three decisions in particular, all decided during the Vietnam War, at least suggested that the High Court might go the other way.

So it did not come as a complete shock when the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals flipped the two lower courts’ results and held that Johnson’s act was speech protected by the First Amendment. “Given the context of an organized demonstration, speeches, slogans, and the distribution of literature, anyone who observed appellant’s act would have understood the message that appellant intended to convey,” the court wrote. “Recognizing that the right to differ is the centerpiece of our First Amendment freedoms,” the court explained, “a government cannot mandate by fiat a feeling of unity in its citizens. Therefore, that very same government cannot carve out a symbol of unity and prescribe a set of approved messages to be associated with that symbol when it cannot mandate the status or feeling the symbol purports to represent.”

Five years had elapsed since Johnson’s initial act of sacrilege when the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear Texas’s appeal, and the passing of time appeared to work in his favor. The first President George Bush had just triumphantly assumed the presidency while America was still in the throes of the collapse of the Berlin Wall. But as freedom flowered in the ashes of the Iron Curtain, censorship debates raged at home and elsewhere. The author Salman Rushdie, who had published his novel The Satanic Verses late the previous year, had a $3 million U.S. bounty placed on his head by Iran’s Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Enraged with the book’s satirical portrayal of the religion’s founder, Mohammed, Muslims everywhere condemned the author and his tome. Several Muslim countries, including Rushdie’s birthplace, India, banned the book, and in February 1989, when Iran’s Ayatollah issued a fatwa demanding Rushdie’s execution as an apostate—calling his book “blasphemous against Islam”—the alarmed writer went underground, living for a time under British-financed security.

The strain between state and art had also intensified in the United States, beginning with hearings held by Congress mid-decade to discuss placing warning labels on obscenity laden music. Tipper Gore had warred with Twisted Sister and recited Prince’s ode to masturbation, “Darling Nikki,” on national TV. It was grand theater. Now, with Russia imploding, emboldened conservatives focused their attention once again on homebrewed battles, this time waging vicious war against federally funded artists and their allegedly sacrilegious representations.

Installations like “The Castration of St. Paul,” consisting of 30 photographs of male genitalia with the names of religious figures under each and, perhaps most famously, Andres Serrano’s “Piss Christ,” a large photograph of a crucifix submerged in a jar of blood and urine, incited outrage. That was only natural. But the consternation was compounded by the fact that they were both funded partly by the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and, thus, used taxpayer dollars. Gnashing of teeth ensued as conservative groups denounced these and other artworks and called for the withdrawal of funding. An art installation, “Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment,” was cancelled because of congressional disapproval of its explicit homosexual material. Politicians in Washington pounced on the issue and pushed for an amendment to the NEA appropriations bill, which prevented the NEA from funding art that was “obscene,” defined as depictions of homo-eroticism, individuals engaged in sex acts, and other acts of a similar nature. President Bush promptly signed the bill upon its 1989 passage.

The flag also made an appearance in the incendiary artistic debate, initiated by a student work at the Art Institute of Chicago in which the aspiring auteur laid an American flag on the floor with an invitation to step on it. Although the creator claimed he wanted to make people think about misplaced patriotism, he instead inspired rancor for his “desecration of the flag.” After tremendous public pressure, including a march by military veterans that ended in a sizable protest outside the Institute, the Illinois state legislature withdrew state funds—to the tune of $64,000 a year—from the Art Institute of Chicago and specifically outlawed the laying of the flag on the floor or the printing of it on shopping bags. [The controversy recalled an incident during the Vietnam War when an artist painted “Flag in Chains” that showed an American flag stuffed with foam rubber and hung in chains. When the painting was shown at the Illinois Art Center, charges were brought against two members of the center’s board of directors. Although convicted in the local courts, the Illinois Supreme Court reversed the decision on the grounds that the artwork had not created a breach of the peace.]

Into this tempestuous cultural cauldron stepped Johnson. Acutely aware of the context his case swirled in, he did all he could to sway popular opinion and, if possible, the Justices’ minds by launching a public relations campaign across the country. “We did an enormous amount of political work,” he recalls. “Myself and the Revolutionary Communist Party initiated a mass committee against what we characterized as forced patriotism.” He, Kunstler, and Cole canvassed the country, speaking at law schools where they were usually shouted down by members of groups such as the Federalist Society until the rest of the student body came to the rescue. “They would get trounced or politically isolated by progressive law students and people that were just outraged that I was convicted or that the issue was even before the courts,” Johnson said.

Whether their efforts contributed to an environment already ripe for such a ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court, in a 5-4 decision, backed the characterization of Johnson’s fire-driven protest as protected speech under the First Amendment. Reaffirming the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, the majority opinion, delivered by Justice William J. Brennan, rejected any interest the state of Texas asserted in preventing the flag burning, finding that it was related to the suppression of Johnson’s expression and therefore unconstitutional.

In ruling for Johnson, Brennan initially scrutinized whether his flag burning should count as expressive conduct under the First Amendment since it involved an act, as opposed to “insulting words.” While the Court admitted that all activity meant to convey a message is not necessarily speech, Brennan wrote that the Supreme Court had “long recognized that its protection does not end at the spoken or written word” and quoted an earlier Supreme Court ruling (Spence v. Washington) to back up his reasoning: “[Our precedents] recognize that a principal ‘function of free speech under our system of government is to invite dispute. It may indeed best serve its high purpose when it induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they are, or even stirs people to anger.”

Spence v. Washington was one of two flag-centered cases the Supreme Court decided in 1974, finding in both that certain types of private use of the flag were constitutionally protected under the right to free expression. Spence was convicted under a Washington flag-misuse statute for affixing a peace symbol onto the flag with black tape. The Supreme Court held that the state’s interest in preserving the physical integrity of a privately owned flag did not outweigh the constitutional protection of the right to free expression.

In Smith v. Goguen, the Supreme Court held that a state statute was unconstitutionally void for vagueness in prohibiting contempt for the flag. Goguen was convicted under a Massachusetts flag-misuse statute for wearing a small cloth version of the American flag on the left rear part of his jeans. The Supreme Court noted that “casual treatment of the flag in many contexts has become a widespread contemporary phenomenon.” Accordingly, the Court held, people have the due process right to be more precisely informed about what is legal and what is illegal under criminal law.

These two formed part of a trilogy of flag-related decisions that were motivated by counterculture distaste for the Vietnam War. The first was handed down in 1969 when the Supreme Court held in Street v. New York that a state regulation prohibiting verbal insults to the flag was unconstitutional. Street was accused of burning the American flag and saying that “we don’t need [it].” The Court held that Street’s words neither urged unlawfulness nor provoked the average person to violent retaliation. In so holding, the Court reaffirmed that “the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits the States from imposing criminal punishment for public advocacy of peaceful change in our institutions.” The Court refused to address the issue of flag burning.

That fell to Brennan in Texas v. Johnson. What the Court had abdicated twenty years later, he gladly addressed, relying on these earlier decisions as well as others—West Virginia v. Barnette (refusing to salute the flag) and Stromberg v. California (displaying a red flag)—where the Court had found restrictions on treatment of the flag unconstitutional. “Johnson was not prosecuted for the expression of just any idea; he was prosecuted for his expression of dissatisfaction with the policies of this country, expression situated at the core of our First Amendment values,” Brennan wrote. There was no doubt in the majority’s mind that Johnson’s demonstrative act was speech. “The expressive, overtly political nature of this conduct was both intentional and overwhelmingly apparent.”

In the process, Brennan couldn’t help but tweak Chief Justice William Rehnquist who crafted a dramatic, emotional dissent emphasizing the historical importance of the flag. In Rehnquist’s opinion (joined by Justices White and O’Connor), the significance of the flag as a symbol of the country outweighed any symbolic speech Johnson’s act could have invoked. “[F]lag burning is the equivalent of an inarticulate grunt or roar that, it seems fair to say, is most likely to be indulged in not to express any idea, but to antagonize others.”

Cutting through this hyperbole, Brennan turned Rehnquist’s logic back on him, using his arguments to stress the unique symbolism and thus the speech the flag represents. “The very purpose of a national flag is to serve as a symbol of our country; it is, one might say (quoting Rehnquist), ‘the one visible manifestation of two hundred years of nationhood.’”

“Pregnant with expressive content,” Brennan lyrically opined, “the flag as readily signifies this Nation as does the combination of letters found in ‘America.’”

Finding that Johnson’s flag desecration was speech, the Court next turned its attention to Texas’s stated interests of “preventing breaches of the peace and preserving the flag as a symbol of nationhood and national unity.” Brennan simply dismissed this assertion by finding that “no disturbance of the peace actually occurred or threatened to occur because of Johnson’s burning of the flag.” Brennan thus reduced the state’s argument to a hypothetical one. “The State’s position, therefore, amounts to a claim that an audience that takes serious offense at particular expression is necessarily likely to disturb the peace and that the expression may be prohibited on this basis.” The Court summarily rejected this argument, relying on precedent “that a principal ‘function of free speech under our system of government is to invite dispute. It may indeed best serve its high purpose when it induces a condition of unrest, creates dissatisfaction with conditions as they are, or even stirs people to anger.” In addition, the Court found that Texas already had a statute specifically prohibiting breaches of the peace.

The Court then narrowed its gaze to whether the State’s stake in preserving the flag as a symbol of nationhood and national unity justified Johnson’s conviction. “Johnson was not…prosecuted for the expression of just any idea,” the Court noted, “he was prosecuted for his expression of dissatisfaction with the policies of this country, expression situated at the core of our First Amendment values.” Moreover, the Court found, Johnson “was prosecuted because he knew that his politically charged expression would cause ‘serious offense.’” Because Johnson’s political expression was targeted for the content of the message he conveyed, the Court found that Texas’s asserted interest was to be held to “the most exacting scrutiny.”

Under this strict standard, the majority found that Texas failed miserably. “If there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable,” Brennan began his summation. Scrolling through previous cases, the Justice concluded that “nothing in our precedents suggests that a State may foster its own view of the flag by prohibiting expressive conduct relating to it.” The Court also found that any support for the state’s asserted interest would favor the restricting of particular viewpoints. “We never before have held that the Government may ensure that a symbol be used to express only one view of that symbol or its referents,” Brennan observed. “To conclude that the government may permit designated symbols to be used to communicate only a limited set of messages would be to enter territory having no discernible or defensible boundaries.”

Brennan emphasized his point, again refuting Rehnquist, by evoking the authors of the country’s greatest document. “[W]e would not be surprised to learn that the persons who framed our Constitution and wrote the Amendment that we now construe were not known for their reverence for the Union Jack.”

In fact, the Court concluded, their decision reinforced the spirit of the Constitution: “We are tempted to say…that the flag’s deservedly cherished place in our community will be strengthened, not weakened, by our holding today. Our decision is a reaffirmation of the principles of freedom and inclusiveness that the flag best reflects…”

Advocates for the absolute preservation of the flag were immediately galvanized. Responding to the clamor, newly elected President Bush called for an amendment to rectify the Court’s assault on “Old Glory.” Congress soon complied, only to be slapped down by the Court a year later in U.S. v. Eichman. In the years since, America’s governing body has repeatedly tried to consecrate the emblem of the United States, even coming within three votes of passage in 1995. This past summer, the House sent another bill the Senate’s way, giving them the opportunity once again to ban political dissent in the form of flag desecration. Although that attempt failed, in a period of war and vicious battle over the meaning of America’s original precepts, the issue is likely to come up again. Perhaps there is no more fitting discourse. “Going back to ’89, a lot of people at the time thought this whole issue was a distraction from war and ‘real’ issues,” Johnson recalls. “I didn’t agree with that. There’s no disputing that the flag is a highly charged political symbol and it’s the content of the symbolism—that’s what the whole battle of my case really brought into greater heightened societal debate.”

DISCLAIMER: THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN OLDSPEAK ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE.