OldSpeak

Is the Bible Still Relevant?

By Joshua Seth Anderson

September 03, 2003

The emergence of a distinct adolescent culture in America over the last 50 years has had many implications for our society, but one of the most obvious ones is this: what’s “cool” if you’re an adult probably isn’t “cool” if you’re 13. And as the marketing department of Thomas Nelson, an evangelical publishing house, discovered when it surveyed teenage girls last year, reading the Bible isn’t exactly a ticket on the adolescent hip train these days because, as the girls reported with typical youthful bluntness, “It’s too big; it’s freaky; and it doesn’t make sense.” However, as Thomas Nelson found out, it’s not impossible for a teenage girl to be a bookworm—especially when it comes to popular magazines like Cosmo, Glamour or Seventeen, which the girls said they loved.

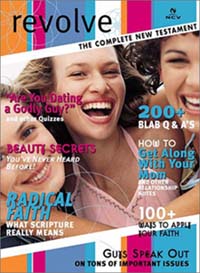

At this point, Thomas Nelson was faced with an obvious dilemma. They wanted to sell Bibles that girls would actually read—but girls thought teen mags were cool and thought Bibles were, well...“freaky.” In the end, they decided to combine the two. The result is Revolve, the decidedly unfreaky New Testament that looks just like a Cosmo except, you know, it’s not. Because while it looks like any number of popular teen mags with its glossy cover and advice columns and photos of hip and attractive teens, this magazine includes all the scripture from Matthew to Revelation—though it might be hard to read the Parable of the Prodigal Son without first taking the quiz entitled “Are You Dating a Godly Guy?” Along with other quizzes, curious girls can find answers to problems like “My crush likes me back, but my friend has a major problem with it!” in Revolve’s advice columns. (“Talk to your friend,” the unnamed guru sagely advises.) In addition, girls will find beauty secrets, scripture commentary and what real guys think about a host of topics, including the importance of school, their ideal girl and how frequently they pray. Interspersed between epistles, monthly calendars also offer daily advice. On September 14, girls are encouraged to “hug your parents a little longer today” and on December 5, “Go watch a football game with some friends. Celebrate our freedom to play!” Assuming a working knowledge of pop culture, the calendars also alert their readers to the birthdays of Cameron Diaz, Eminem and Britney Spears, among scores of other pop luminaries, instructing girls to pray for them and other “persons of influence.” So far, the hip Bible formula seems to be working. Revolve is due for a second printing only months after it was first released and currently ranks 57th in all book sales on Amazon.com.

At this point, Thomas Nelson was faced with an obvious dilemma. They wanted to sell Bibles that girls would actually read—but girls thought teen mags were cool and thought Bibles were, well...“freaky.” In the end, they decided to combine the two. The result is Revolve, the decidedly unfreaky New Testament that looks just like a Cosmo except, you know, it’s not. Because while it looks like any number of popular teen mags with its glossy cover and advice columns and photos of hip and attractive teens, this magazine includes all the scripture from Matthew to Revelation—though it might be hard to read the Parable of the Prodigal Son without first taking the quiz entitled “Are You Dating a Godly Guy?” Along with other quizzes, curious girls can find answers to problems like “My crush likes me back, but my friend has a major problem with it!” in Revolve’s advice columns. (“Talk to your friend,” the unnamed guru sagely advises.) In addition, girls will find beauty secrets, scripture commentary and what real guys think about a host of topics, including the importance of school, their ideal girl and how frequently they pray. Interspersed between epistles, monthly calendars also offer daily advice. On September 14, girls are encouraged to “hug your parents a little longer today” and on December 5, “Go watch a football game with some friends. Celebrate our freedom to play!” Assuming a working knowledge of pop culture, the calendars also alert their readers to the birthdays of Cameron Diaz, Eminem and Britney Spears, among scores of other pop luminaries, instructing girls to pray for them and other “persons of influence.” So far, the hip Bible formula seems to be working. Revolve is due for a second printing only months after it was first released and currently ranks 57th in all book sales on Amazon.com.

Asinine dating advice aside, Revolve’s attempt at teenage hipness raises significant and timely questions about the ways the contemporary evangelical church pursues relevance in today’s culture. Everywhere, evangelicalism can be found imitating popular secular forms, from Christian “boy bands” to Christian pop fiction (Left Behind) to the whole “seeker-friendly” worship style that has become immensely popular at many community churches. But often this wholesale pursuit of cultural consequence and less offensive faith (“unfreaky” Bibles or more “personal” worship) has led to superficial expressions of Christianity which, ironically, lack real substance. Like a puppy chasing its tail, the more the church pursues relevance, the less truly relevant it becomes. What we are missing is that the pursuit of relevance is unnecessary. In fact, the Good News of Jesus’ life and death and resurrection is, by definition, relevant to each human life—for it provides hope for every human problem or question. When the writers of the Westminster Catechism asked “What is the chief end of man?” they were not attempting to assert the gospel’s relevance to their culture. Rather, they were simply operating under the understood assumption that the Good News of Christ is both inherently and utterly relevant to human life.

And this is the truth that much of current evangelicalism and the creators of Revolve seem to have forgotten: the gospel of Jesus does not need human assistance to attain relevance. Certainly we must present God’s eternal truth clearly and in language that is easily understood by the culture around us. But when we dress Christianity in the costume of Seventeen or Cosmo, we dismissively patronize teens who need the fullness of the gospel, not “Godly” dating advice or beauty secrets. For while it is impossible for us to add relevance to the gospel of Christ, it is possible for us to distort the gospel in such a way as to make it ultimately irrelevant to our culture. And that is what has happened with Revolve. The message within its glossy pages is not that we are “strangers in a strange land,” as Hebrews records, but that Christians can delight in the antics of Britney Spears along with the rest of the world—we should just pray for her, too. And God does not so much transform our lives as He condones them (and perhaps even provides some helpful advice along the way).

As Os Guinness argues in his recently published Prophetic Untimeliness, which provides a wise (and far more thorough) discussion of this topic, in order to maintain true relevance to human hearts, Christians must preach the whole gospel, even the “freaky” parts. He writes,

Emphasize only the natural fit between the gospel and the spirit of our age and we will have an easy, comfortable gospel that is closer to our age than to the gospel—all answers to human aspirations, for example, and no mention of self-denial and sacrifice. But emphasize the difficult, the obscure, and even the repellent themes of the gospel, certain that they too are relevant even though we don’t know how, and we will remain true to the full gospel. And, surprisingly, we will be relevant not only to our own generation but also to the next, and the next, and the next.

Like most great Biblical truths, this is a human paradox—but it is true. Just as it is the meek who will inherit the earth and the weak who are truly strong, today’s Christians are most relevant when we abandon modern ideas of relevance, even as this dooms us to apparent irrelevance. Our call is not to imitate our culture, but to subvert it. And like Gideon’s army of three hundred that defeated one hundred thirty thousand Midianites, it is not our numbers or relevance which matters, but only our faithfulness.

DISCLAIMER: THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN OLDSPEAK ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE.