OldSpeak

“I Am an Audience” : The Sensual Sustenance of Richie Havens

By Jayson Whitehead

February 07, 2008

|

|

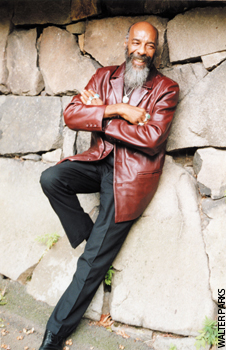

Richie Havens

|

I saw Richie Havens perform in the early ’90s in a small club in Alexandria, and arrived early enough to sit in the front row and watch him play guitar up close. Havens has massive hands that he uses to bar up and down the fret, and uses his thumb to press down over the neck and onto the strings. While doing so, he strums swiftly and rhythmically as he sings of “Handsome Johnny” or “Freedom,” the song he rocked Woodstock with. It all makes for an entrancing experience, his raspy voice and jangling guitar spreading out like luminescent waves of sound.

“I started out in doo wop, which is pure harmony,” explains the 67-year-old Havens, who performs at the Gravity Lounge on February 7, during a phone interview. After quitting doo-wop, Havens became a part of the Greenwich Village beatnik scene and, while sitting inside a small folk club one night, was approached by its owner, a musician named Fred Neil. “Richie, you’ve been singing my songs from the audience, in harmony no less,” Neil said to him. “Take this damn guitar home and learn to play it yourself.”

Three days later, Havens came back with a new instrument and a style of playing that was unusual and unique. “I never think about my guitar playing as guitar playing,” he says. “I do find little strings that I can let go of within the chord that would give me a ‘sus’ [suspended, a type of chord] feeling. Having that, I think, really, truly draws your voice out.”

“I’m in the communications business,” he says, and one of the first songs he chose to communicate with during his first gig was a tune he heard from another folksinger named Gene Michaels. “I heard him play it onstage and it just blew my mind, so I asked him to write it down for me, and I assumed he wrote it,” Havens remembers of “A Hard Rain’s a’Gonna Fall.” It took him eight days to master what was actually a Bob Dylan composition, and he debuted it days later at his first big hootenanny at Gerde’s Folk City. “When I got off the stage, they applauded so loud it scared the heck out of me,” he says, so Havens headed for the exit but not before encountering a young guy in the hall. “He’s got tears in his eyes, and he says to me [all choked up], “That was my favorite version of that song, man. I really loved it.’” When Havens got to the door, another folksinger pointed at the guy he’d just talked with. “He wrote that damn song you just sang,” he said. “That’s how I met Bob Dylan,” says Havens, guffawing. “It blew my mind.”

Ever since, Havens has been a keen interpreter of Dylan’s music, which is how I discovered Havens, through a cover of “Just Like a Woman.” “I thought he was such a profound poet,” says Havens of the mercurial Dylan, and while it was the language that originally drew him in, “the fact that he had already put melody together with it made it so easy for me to get a hold of.” That affiliation led to his most recent output, a version of “Tombstone Blues” for the I’m Not There soundtrack.

I have that on my iTunes library, plus a vinyl record somewhere of his 1970 album, Alarm Clock, that opens with a live version of George Harrison’s “Here Comes the Sun.” For over a minute, Havens rips furiously at his strings while a bass, pedal steel and conga drum jam behind him. Then Havens comes in. “Little darling…”

“I think I’m singing the song the way the original person gave it to me,” Havens reveals. In order for the song to fit his style, Havens might speed it up or slow it down, but “for the most part I never really change the chords of it,” he says. “They just have a sensual sustenance going through them.”

According to him, when Havens takes the stage he only knows the first and last song he will perform. “I know what those two songs are gonna be, and I’ll go up and sing the first song,” he says, likening the process to a Yoga breathing technique. “I will work out on the stage, and they will then applaud, so they will exhale and I will inhale.” On and on that goes, exhale, inhale. “You’re being moved by a sense from the audience,” he explains. “It’s not by word; it’s that they’re listening and they’ve already applauded about how they’ve felt for the previous song. Automatically, the next title just comes up in my brain.”

The second time I saw Richie Havens was just a couple years ago at the now-closed Starr Hill. I was in back by the bar, too far away to get much from it, and ended up leaving halfway through. This time I will show up early to get up close and feel some of what Richie Havens is giving off, the same type of energy he dispensed to the hundreds of thousands at the 1969 Woodstock festival or to the few hundred that might fit into the Gravity Lounge. “I think I’m an audience,” Havens says. “I get to hear what comes through me at times when I don’t know what is going to come through me. It keeps me very much alive and feeling for these songs.”

DISCLAIMER: THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN OLDSPEAK ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE.