OldSpeak

Gospel of the Living Dead: George Romero’s Vision of Hell on Earth: An Interview with Kim Paffenroth

By John W. Whitehead

October 03, 2008

Zombies partially eat the living. But they actually only eat a small amount, thereby leaving the rest of the person intact to become a zombie, get up, and attack and kill more people, who then likewise become zombies. Zombies derive no nourishment from eating people, since they function exactly the same even if they don’t eat, and they never tire or sleep or slow down, regardless of their diet or lack of it; so the whole theme of cannibalism seems added for its symbolism, showing what humans would degenerate into in their more primitive, zombie state. As the series of movies progresses, this theme becomes more and more prominent: we, humans, not just zombies, prey on each other, depend on each other for our pathetic and parasitic existence, and thrive on each others’ misery.—Kim Paffenroth, Gospel of the Living Dead

When people speak of zombie movies today, they’re really talking about movies that are either made by or directly influenced by one man, director George A. Romero. Now an avuncular, grandfatherly figure with thick glasses and a big smile, it is difficult to imagine Romero crafting images of such horror and grotesquery. His movies and their related progeny are enormously popular in the United States and even more so worldwide, despite their very low budgets and lack of any bankable stars. Only Romero’s most recent, Land of the Dead (2005), and the remake of Dawn of the Dead (2004), included even B-list actors.

|

|

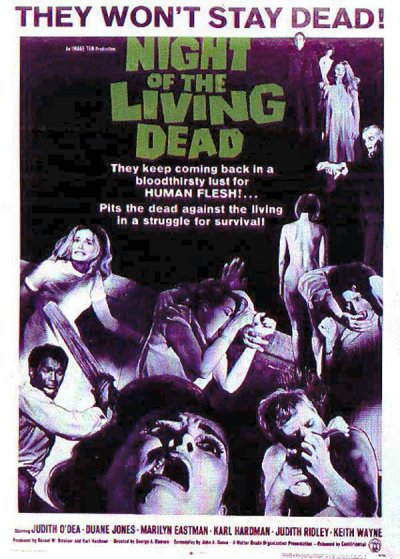

Romero’s landmark film Night of the Living Dead (1968) has defined the zombie genre since its release and has even spilled over into the depiction of zombies in any medium, including books, comic books, video and board games and action figures. Sometimes the influence can come full circle: Romero-influenced zombies populate the immensely popular and violent video game Resident Evil, which was made into films (2002 and 2004), and also influenced the remake of Dawn of the Dead, which some critics then accused of looking too much like a video game.

Although Romero is said to eschew the idea that his movies have meaning or significance, they are widely acknowledged, by reputable critics and not just fans, to be thoughtful and serious examinations of ideas, not just exercises in shock and nausea. Even the gruesomeness and violence may be a vehicle for catharsis rather than sadistic voyeurism. That’s because Romero uses horror more in the tradition of American Gothic literature, which includes such luminaries as Edgar Allen Poe, Herman Melville and Flannery O’Connor, where shocking violence and depravity disorient and reorient the audience, disturbing them in order to make an unsettling point, usually a sociological, anthropological or theological one.

Kim Paffenroth is a recognized authority on Romero, his influence and his films. He is a professor of religious studies at Iona College and is the author of several books on the Bible and Theology. Dr. Paffenroth attended St. John’s and Harvard Divinity School and received his doctorate from the University of Notre Dame. As he describes the experience, “Starting in 2006, I had one of those strange midlife things and turned my analysis towards horror films and literature.” He has written Gospel of the Living Dead: George Romero’s Visions of Hell on Earth (Baylor, 2006), which won the 2006 Bram Stoker Award; Dying to Live: A Novel of Life Among the Undead (Permuted Press, 2007); Orpheus and the Pearl (Magus Press, 2008); and Dying to Live 2: Life Sentence (Permuted Press, 2008).

Dr. Paffenroth took a few minutes out of his busy schedule to discuss the importance of George A. Romero’s apocalyptic vision.

|

|

John Whitehead: George A. Romero is generally given credit for the proliferation of zombie movies, but there were some 40 zombie movies before Night of the Living Dead in 1968. What makes Night of the Living Dead different than, for example, I Walked with a Zombie or some of the other great zombie movies that preceded it?

Kim Paffenroth: A lot of people call Romero the creator of the zombie genre, but you’re right. It is more accurate to call him the person who resuscitated the genre. It is pretty widely acknowledged that by the end of the 1960s, the zombie genre had sort of played itself out. What Romero did was add a certain spin to it, so much so that all the zombie films that followed his 1968 classic very much resemble it. Romero is the one who added the whole aspect of cannibalism—that is, zombies eat people. Thus, the zombies are not simply mindless beings who are under some kind of mind control or voodoo and don’t know what they’re doing. Now, since Romero, they really are monsters possessed with an insatiable appetite to kill and eat people. It is that consuming aspect that Romero takes up in Dawn of the Dead, which later followed Night of the Living Dead.

JW: When Romero made Night of the Living Dead, do you think he had an overriding philosophy? Or do you think he was simply making a movie? Was Romero beginning the philosophical journey that would determine every zombie movement after 1968?

KP: It would be too much of a coincidence if he had none of the ideas in mind that he would later explore. On the other hand, I doubt that Romero had the whole, full-blown mythos in mind when he decided to make the movie. Certainly, any moviemaker, playwright or whoever with certain abrasions, especially with a movie where it cost considerable funds to make a piece of art, does have to adapt. Thus, in many ways, he was just being practical.

JW: Night of the Living Dead, like a lot of the movies of its time, came out in the middle of the Vietnam War. With all the turmoil over that war, the same kind of theme of the country being at war abroad and at home comes into play. It was man versus man. The figure of the zombie was a perfect unmarked, allegorical figure. It was moving in from all sides. The whole country was going crazy at the time over who was and who was not the enemy. Do you think that had an impact on Romero’s philosophy?

KP: That is another of Romero’s real strengths. He was able to take primal, timeless fears—such as the fear of being dead, the fear of sinking into anonymity and merely being one of the crowd—and encapsulate a lot of them in the zombies. At the same time, he kept giving us these tales at about ten-year intervals that very much capture the mood of the particular time period. Night of the Living Dead captures the fears of the Vietnam era. Dawn of the Dead captures the fears of the late ‘70s, materialism and American consumer culture. Day of the Dead captures the fears of the military-industrial complex. Land of the Dead is a swipe at the Bush Administration. That is what makes a great artist—he is timeless while being particularly timely and suited to the moment when art is produced.

|

|

JW: Romero said that his movies are a cinematic journey and a chronicling of the times. But great directors of the past such as John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock did the same thing. Do you believe Romero ranks as a great director? Or is he more of a popularizer of a genre?

KP: Good question. You would get both answers, even from people who much admire and enjoy his work. Romero is far enough ahead of other horror directors that he will rank with the top makers of not just genre films, but of directors in general. The way Romero handles the material and even technical things like camera angles says that he is really a master craftsman.

JW: Romero is an originator basically of a particular kind of film. As you said, he introduced the idea that zombies are cannibals. They eat the living. The whole theme is cannibalism. Does that symbolize Romero’s vision that American culture is becoming primitive and is regressing? In Day of the Dead in 1985, the last scenes are just people eating guts. What is Romero trying to say there? Why is cannibalism such a strong theme in the zombie movies?

KP: As I said, Romero has both that timeless and that particularly pointed timely quality. The timeless sense is tied to more long-lasting representations of sin. Part of the essence of sin and evil from a traditional standpoint is that it is self-destructive. It feeds on itself. It’s parasitic. Thus, cannibalism fits that image of damnation and the walking damned milling around outside. It fits that longstanding tradition of representing monsters and evil. At the same time, especially with Dawn of the Dead, Romero wanted to tie bestiality and primitiveness together with the descent into self-consumption. We are amusing, shopping and eating ourselves up, as well as, of course, exploiting other groups for our own advancement, even though it doesn’t really do us much good. One of the prominent images in Dawn of the Dead is that it is not just the zombies who are zombified. But once they are zombified, they go to the mall. And that is the other big image Romero includes in that movie.

JW: You use terms like sin and evil. Is Romero in any way spiritual or religious? What is his background? And why would he be addressing issues like this?

KP: He was raised Catholic, although he has distanced himself from that. But even in our very secular culture, you pick up some of those religious elements as part of your vocabulary, especially if you are raised in a traditional Catholic family. You are going to pick up on those images, even if you ultimately reject the metaphysics behind them. In the depiction of evil as sin, religion does have an impact on how you envision it.

JW: Over time, artists have sometimes touched on overtly Christian themes without knowing it. Are you saying that is true of Romero?

KP: Yes. In a very inclusive way, Romero’s message feeds into questions that I think are of interest and of importance to Christians. And, as you say, whether he intended that, it still may well be there. In other words, looking at his work isn’t like looking at a C.S. Lewis or Tolkien work where you have an overtly Christian author trying to weave these themes in there.

JW: In Dawn of the Dead, one of the characters near the end of the film looks at the zombies and says, “They’re us.” This brings me to the mall culture and materialism. There are more malls in the United States than churches or synagogues, and people spend more time in the malls than they do in houses of worship. Thus, Americans have become materialistic consumers. We, in effect, consume ourselves to death. It seems to me that one of the overt messages in that film is that there really is no difference between humans and zombies. Are we all zombies?

KP: Ultimately, that is the point. That, in a way, is a joke that pervades all the zombie movies. Humor is throughout the films. Of all the great movie monsters, zombies are the funniest. You just love to watch them. You laugh when they stumble around, but the joke folds back on us. We do the same thing when we wander around mindlessly in the mall, which we all do, whether we are college professors or not. Everybody goes to the mall. That is part of Romero’s wit. It is a social criticism. Although done in a light-hearted way, it is still a fairly pointed accusation at humans. Romero’s films are really about the empty, meaningless lives that we lead. This includes the mindless activity of shopping.

JW: We’ve moved away from the spiritual aspect of people. Is that what Romero is saying?

KP: Like everyone else, I go to the mall. But I prefer going for a walk in the woods or whatever it is that you commune with. That would be better than staring at things we can’t afford at the mall.

JW: There are those who believe that we face a spiritual crisis in this country. Much of Christianity has gone that way. Christian television is so materialistic. There is the Prosperity Gospel, which says that Christians are on earth to get rich. This is despite the fact that the founder of Christianity, Jesus Christ, was an aesthetic who did not have any money. It seems to me that American culture has basically thrown over true spirituality for false religion, which is materialism.

KP: That is a great way to put it. I often find that the purveyors of Christianity are delivering what, to me, is a much emptier message. And the Prosperity Gospel is the most strange and least appealing. I believe deep down that God wants my well-being, but I don’t see God wanting me to be rich or cheering me on when I go and pursue wealth and material things. The irony is that Romero, who has in many ways left Christianity, is the one who mockingly points the finger at us and says, “You have lost the real path. You are the materialistic ones.” We all are. And his message, even though it might be mocking from an outsider, is a very helpful salutary warning to us all.

JW: In your book Gospel of the Living Dead you write, “The ability of the zombies to wreak so much havoc so quickly, and the human’s ineffective response to the threat, show that in each case the society is rotten from within to begin with.” Then you note that Romero and other filmmakers use the fantastical “disease” of zombies to criticize the very real diseases of racism, sexism, materialism and individualism that would make any society easy prey for barbarian hordes. What do you mean by this? Is America still like that? There are those who say that America has gone beyond these things. But have we really?

KP: I don’t think we have. I still fear that our society is sometimes a little more embarrassed about such social diseases and hides it a little bit better than we used to. But we are still very fractured along all those lines of race, class, gender and even just the general one of individualism. I don’t know how neighborly we always are. I am not known to admit it to my own life. I am not that close to my neighbors.

JW: We have lost community life in America. Some argue that community can be found in the mall, but malls aren’t community.

KP: Malls are a lot of people alone in the same vicinity. When I’m at the mall, I see people walking together side by side, and they are both talking on a cell phone.

JW: Such behavior has caused one author to say that Americans are some of the loneliest people on the face of the earth.

KP: They’re on cell phones so I assume they’re not talking to each other. They are talking to some invisible person somewhere else, and you just want to say, “Put down the cell phone and talk to this person right here next to you that you are practically in physical contact with.” That has been Romero’s mocking point all along, and it reaches an absurd level in one of his recent films where people throughout the movie are constantly holding a web-cam or a cell phone camera and photographing the mayhem. Everybody in the theater is yelling at the screen, “Put down the phone and help this person who is getting torn to pieces by zombies.”

JW: There is the “bystander effect.” For example, there was an incident in a convenience store where someone had a heart attack. The people shopping in the store actually stepped over the person to pay for their purchases and walked out, without even stopping to help her.

KP: It is a very frightening and, I fear, an all-too-common event. And then there are car accidents where people actually get their cell phone out to take a picture of it.

JW: What you are saying is that all the things that have plagued American society in the past are still with us. I see it on a daily basis. We try to pretend it doesn’t exist. Thus, anyone who watches a Romero movie must be prepared for a strong indictment of modern America. And you say it is a critique that could be characterized as broadly Christian. What do you mean by that?

KP: That goes back to your earlier point. When we are consumed by consumerism, materialism and are lost in a fractured community where we can’t help one another, we have trouble feeling compassion and coming to the aid of one another in a crisis.

|

JW: Christianity is supposed to stand for compassion.

KP: Christians are supposed to stand for those things. As you said, too much of modern Christian piety is not offering a criticism of our culture but is instead cheerleading our culture either in its wars or in its very materialistic values. I see it as ironic. But still I see it as a fundamentally useful and helpful message, even if a nonChristian delivers the warning that this is where we are headed as a society. I certainly applaud Romero for that over and over.

JW: One of your favorite books is Dante’s Inferno. You write that Romero’s zombie movies, either consciously or unconsciously, have borrowed from Dante’s theme in Inferno. They’ve picked up on Dante’s greatest and most surprising notion that hell is not a place of external torments. Instead, hell is primarily of our own making. It is endless boredom and repetition and lack of fulfillment in life. Are Romero’s movies saying that hell is here on earth? Is hell here and now?

KP: Yes. Romero’s movies are broadly Christian. Some ask, “Where is the hopeful part? Where is the resurrection? Where is salvation?” My response is that Romero is focusing on that part of the Christian message which says human beings on their own would go straight to hell. Human beings get endlessly fascinated by bright shiny objects or by hurting one another. We pursue materialistic goods and forget the higher good of either God or even just loving and helping one another. Romero definitely is the dark side of the Christian message. Dante is a pretty good place to start for that as well.

JW: What’s your own theological theme? Do you think hell is simply internal? Do you agree with Dante?

KP: I agree with the depiction. One of the things that outsiders always have against Christianity is the question of literal hell. How could an all-loving God hurt people like that? How could God torture people forever? Wouldn’t God eventually want to forgive them? Dante puts it the right way. And Romero gives the zombie version of Dante’s philosophy, which is, “God isn’t doing anything to the damned. They are just being left to their own.”

JW: God simply leaves people to their own devices? In the end, hell is separation from God?

KP: Yes. They are left to their own ends, which are empty, meaningless and painful, but that is what they chose. When I read Dante during my sophomore year in college, Christian doctrine suddenly made a lot more sense to me.

JW: But don’t we have hell right here on earth? Look at the tragedy of Darfur. Look at Iraq, where thousands upon thousands of innocent civilians have been blown to pieces. Look around the world. In most of the world, people are living in a form of hell. Even in some parts of this country, the way the poor are treated and the way they live is a semi-state of hell.

KP: Exactly right. Hell is not a place where God’s vengeance rains down on people. Hell is simply a place that is insulated from God’s love and insulated by the people who end up there. And as you say, there are plenty of places of outright hell on earth, but many others are actively insulating themselves from God all the time and further and further creating a hell. That’s another thing that is often observed. The things that go on in zombie movies aren’t nearly as frightening. And they are not nearly as grotesque as the things that go on in real life.

JW: Romero’s great trilogy is made up of Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead and Day of the Dead. Day of the Dead, which came out in 1985, concludes with a massive feast that is easily the goriest scene Romero ever directed. Intestines, stomach, cartilage and innards of all sorts are ripped apart and slurped down in nasty, gruesome detail. Is this what is finally left of Romero’s vision of America? Is America not just destroyed, not just wiped out, but desecrated?

KP: Day of the Dead is certainly his darkest indictment of America. Even some of the dialogue earlier in the movie that describes what is going on there is of prime importance. In that movie, the people are trapped in a storage facility. Oddly enough, this time it is not a mall but a storage facility where, as one character describes, everything is stored there— every movie ever made, every book ever written, and so on. Then he starts listing some odder things—every tax form, every tax return ever filed and every census report. Romero says, “We need to leave here and just seal it up like a tomb and just forget about it.” The darker, grimmer part of Romero’s vision is that we tried the whole American experiment, and now it is over. It is dead. Let us just seal it up like a pyramid, as the Egyptians would. Let us just seal it up and let the sands cover it and try something else.

DISCLAIMER: THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN OLDSPEAK ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE.

Dr. Kim Paffenroth, Associate Professor of Religious Studies and author of apocalyptic, zombie horror.

Dr. Kim Paffenroth, Associate Professor of Religious Studies and author of apocalyptic, zombie horror.