OldSpeak

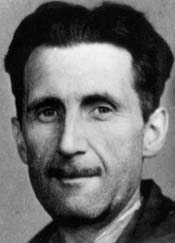

Down With Big Brother: The Thought Crimes of George Orwell

By John W. Whitehead

October 07, 2002

"What I have most wanted to do throughout the past ten years is to make political writing into an art. My starting point is always a feeling of partisanship, a sense of injustice. When I sit down to write a book, I do not say to myself, "I am going to produce a work of art." I write it because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention, and my initial concern is to get a hearing." – George Orwell, Why I Write (1947)

|

George Orwell was the pen name Eric Blair took in 1934. At the time of his death in England in 1950, 46-year-old Orwell had been a writer for less than twenty years. For about half of that period, he had been obscure and poor. Orwell’s life was never a comfortable one. He was shot in the throat while fighting in the Spanish Civil War and suffered from a demoralizing and ultimately lethal case of tuberculosis. All the while, Orwell lived on a low budget and, whenever possible, tried to grow his own food and even make his own furniture.

It was only with the publication of Animal Farm in 1946 that Orwell’s name began to surface as a universal anthem against totalitarianism. But as with most of Orwell’s onerous life, Animal Farm almost did not see the light of print. Many publishers rejected it because it was believed the book would have a disturbing influence on Soviet-American relations.

By 1949, with the appearance of 1984, Orwell cemented his name in history. 1984 is the story of one man’s nightmare odyssey through a world ruled by warring states and an authority structure that controls not only information but also individual thoughts and memories. Against the Fascist backdrop of the Republic of Oceania, Winston Smith, a minor bureaucrat, joins a covert group and pursues a forbidden love affair only to become a hunted enemy of the state and of Big Brother.

No doubt 1984 was Orwell’s most important book. It is the only English contribution to the literature of twentieth-century totalitarianism that can stand with the likes of Alexsandr Solzhenitsyn, Arthur Koestler and others. With a stunning clarity and edge, it uncovers the living roots of totalitarianism in contemporary thought and speech. Orwell, however, was not simply writing about the horrors of Stalinist Russia. His words were pointed at the West as well and the deadening avalanche of materialism. Of course, with advances in technology and the ever-increasing penchant for government surveillance, the situation has worsened since Orwell’s time. Certainly Newspeak and Doublethink, two terms Orwell added to the English language, describe the current wall-to-wall propaganda of the military-industrial-entertainment complex in which reality and truth are manufactured by the managerial elite and where, under the right circumstances, the masses can be made to believe that 2+2=5.

Orwell would probably be surprised to learn that he is still being read at the dawn of the third millennium and that people still have the capacity to think at all. As he recognized in Homage to Catalonia (1938), an account of his time in the Spanish Civil War of the late 1930s and the government manipulation of history, "This kind of thing is frightening to me, because it often gives me the feeling that the very concept of objective truth is fading out of the world." Orwell reworked this concept in 1984.

Orwell is more relevant now than he was when he was alive. He had the uncanny foresight to realize that although we present our society as one of freedom, individualism and idealism, these are, in reality, mostly words. Our society is, in fact, a centralized bureaucratic managerial industrial entity motivated primarily by a crass materialism that is mitigated only slightly (if at all) by any spiritual, religious or esoteric concerns. All it takes is a tragedy, such as the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, to make America show its real colors. Within hours, as society began to implode, Americans were willing to sacrifice their most sacred freedoms for a promise of security–amazingly from the very government that had failed to protect them.

The managerial elite quickly seized the moment, as the blueprint that was laid down for a police state within months of the terrorist attacks illustrates. In reaction, the U.S. government passed invasive and overreaching legislation that invites intrusion into the everyday lives of American citizens. For instance, the massive USA Patriot Act, which was rushed through Congress (although the majority of congressmen admitted they had not read a word of it) allows, among many other things, clandestine "black bag" searches for medical and financial records, computer, Internet and telephone communications and even the books Americans borrow from the library. The Act also merged the FBI, CIA and other clandestine agencies into a domestic and international secret police, all equipped with paramilitary forces. The power and authority now possessed by the U.S. government to investigate the average citizen is unparalleled in history. Moreover, this same sort of draconian legislation is being established in the European Union. Thus, the entire West has now come under the pall of a police state mentality.

Add to this the fact that surveillance cameras have sprung up virtually everywhere. Government cameras stare at us from stoplights; they spy on our children at school and peer at us on street corners, in public parks and in public buildings. Many private companies also use these systems (which can be accessed by the government) to keep an eye on their property and their employees. The surveillance cameras are often so tiny that they fit into the smallest openings. The plain and simple truth is that we are all being watched. As Orwell writes in 1984:

There was of course no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment. How often, or on what system, the Thought Police plugged in on any individual wire was guesswork. It was even conceivable that they watched everybody all the time. But at any rate they could plug in your wire whenever they wanted to. You had to live–did live, from habit that became instinct–in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and, except in darkness, every movement scrutinized.

Orwell also confronted the most pressing issue we presently face, one that raises important philosophical and religious issues. In the words of Erich Fromm, from his afterword to 1984 (Harcourt Brace, 1983), "Can human nature be changed in such a way that man will forget the longing for freedom, dignity, integrity and for love?" Can we forget that we are human? Or does human nature have an innate dynamism that will attempt to change an inhumane society into a human one?

Orwell recognized that by destroying standard language (that is, "Oldspeak") and reformatting it into what he termed "Newspeak," humanness could be reduced to an infinitesimal pinprick. The fact that people have freedom and equality and therefore worth and dignity would be lost in a world distorted by Newspeak. As Orwell writes in his appendix to 1984:

One could, in fact, only use Newspeak for unorthodox purposes by illegitimately translating some of the words back into Oldspeak. For example, All mans are equal was a possible Newspeak sentence, but only in the same sense in which All men are redhaired is a possible Oldspeak sentence. It did not contain a grammatical error, but it expressed a palpable untruth, i.e., that all men are of equal size, weight, or strength. The concept of political equality no longer existed, and this secondary meaning had accordingly been purged out of the word equal.

Thus, Orwell continues, "a person growing up with Newspeak as his sole language would no more know that equal had once had the secondary meaning of ‘politically equal,’ or that free had once meant ‘intellectually free,’ than, for instance, a person who had never heard of chess would be aware of the secondary meanings attaching to queen and rook."

In such a state of existence, there can be no appeal to history for meaning. "You must stop imagining that posterity will vindicate you, Winston," O’Brien instructs Smith while torturing him in 1984. "Posterity will never hear of you. You will be lifted clean out from the stream of history. We shall turn you into gas and pour you into the stratosphere. Nothing will remain of you: not a name in a register, not a memory in a living brain. You will be annihilated in the past as well as in the future. You will never have existed."

The destruction of language annihilates links with the past and ultimately leads to the eradication of human nature. Orwell strikes at the heart of the matter in this exchange between O’Brien and Winston Smith:

"There is a Party slogan dealing with the control of the past," he said. "Repeat it, if you please."

"’Who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past,’" repeated Winston obediently.

"’Who controls the present controls the past,’" said O’Brien, nodding his head with slow approval. "Is it your opinion, Winston, that the past has real existence?"

And where does the past exist? "In the mind. In human memories," Smith answers. To which O’Brien retorts, "In memory. Very well, then. We, the Party, control all the records, and we control all memories. Then we control the past, do we not?"

"If you want a picture of the future," O’Brien opines, "imagine a boot stamping on a human face–forever." Orwell’s mood, therefore, was one of near despair about the future of the human race. Will we become soulless automatons and not even be aware of it? Will we be able to discern truth anymore? Or will we inexorably fall prey to the overlords of society and the language of Newspeak?

The three Newspeak slogans of the government in 1984 are reminiscent of the present military-industrial-entertainment complex:

WAR IS PEACE

FREEDOM IS SLAVERY

IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH.

Most of Orwell’s insights on developing authoritarianism stem from several incisive observations on war. First, he shows the economic significance of continuous arms production and the building of a war machine–something without which the economic system cannot function. This, of course, leads to an inordinate influence of the military on an otherwise democratic society–something Dwight D. Eisenhower warned of as early as 1961 in his Farewell Address:

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.

We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.

Furthermore, Orwell gives us an oppressive picture in 1984 of a society that is constantly preparing for war, constantly afraid of attack (for example, by terrorists) and perpetually preparing to find the means of complete annihilation of alleged opponents. Orwell argues persuasively that we cannot retain any semblance of freedom and democracy under such circumstances. In the end, the military will become (in fact, if not in law) the dominant force in society, especially when it is combined with monolithic commercial interests.

Orwell’s influence has been widespread. As Christopher Hitchens notes in Why Orwell Matters (Basic Books, 2002):

It only remains to be said that in 1953–three years after Orwell’s death–the workers of East Berlin protested against their new bosses. In 1956 the masses in Budapest followed suit, and from 1976 until the implosion of the ‘people’s democracies,’ the shipyard workers of Poland were the celebrated shock troops who mocked the very idea of a ‘workers’ party.’ This movement of people and nations was accompanied by the efforts and writings of many ‘exile’ and ‘vagrant’ intellectuals, from Milosz himself to Václav Havel, Rudolf Bahro, Miklós Haraszti, Leszek Kolakowski, Milan _imečka and Adam Michnik. Not one of these failed to pay some tribute to George Orwell.

George Orwell has much to say to us. Unfortunately, however, many have never read his writings. This includes the overwhelming majority of young people, their minds sapped by a lifeless education system and the mediocrity of modern entertainment.

Sadly, Orwell has had no lack of critics. According to the American Library Association, 1984 has been one of the most targeted books for banning. Orwell’s name has also rumbled from the bowels of political correctness because of some of his views. As Hitchens writes:

It is true on the face of it that Orwell was one of the founding fathers of anti-Communism; that he had a strong patriotic sense and a very potent instinct for what we might call elementary right and wrong; that he despised government and bureaucracy and was a stout individualist; that he distrusted intellectuals and academics and reposed a faith in popular wisdom; that he upheld a somewhat traditional orthodoxy in sexual and moral matters, looked down on homosexuals and abhorred abortion; and that he seems to have been an advocate for private ownership of guns. He also preferred the country to the town, and poems that rhymed.

Orwell was not a saint. In fact, he once said that "sainthood is a thing human beings must avoid." But as Richard H. Rovere notes in his introduction to The Orwell Reader (Harcourt, 1984), Orwell "was an uncommonly decent person, and his moral and physical courage survived many hard tests."

Orwell was a great believer in what he considered to be normality. This is not to say that he despised the extraordinary person (of which he was one). However, he detested conformity, and he never celebrated mediocrity. "The average sensual man is out of fashion," Orwell once wrote, and he proposed to restore him, giving him "the power of speech, like Balaam’s ass" and uncovering his genius. Orwell was the champion of the common man–those trapped in the everyday existence with little, if any, hope of escape.

Orwell took the supposedly Christian virtues and showed how they could be lived. And his life and ideas have been vindicated by time. What Orwell illustrates "by his commitment to language as the partner of truth," writes Hitchens, "is that ‘views’ do not really count; that it matters not what you think, but how you think; and that politics are relatively unimportant, while principles have a way of enduring, as do the few irreducible individuals who maintain allegiance to them."

DISCLAIMER: THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN OLDSPEAK ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE.