OldSpeak

Crazy for God: An Interview with Frank Schaeffer

By John W. Whitehead

October 23, 2007

The public image of the leaders of the religious right I met with so many times also contrasted with who they really were. In public, they maintained an image that was usually quite smooth. In private, they ranged from unreconstructed bigot reactionaries like Jerry Falwell, to Dr. Dobson, the most power-hungry and ambitious person I have ever met, to Billy Graham, a very weird man indeed who lived an oddly sheltered life in a celebrity/ministry cocoon, to Pat Robertson, who would have had a hard time finding work in any job where hearing voices is not a requirement.—Frank Schaeffer, Crazy for God

By the time I met Frank Schaeffer, I had read all of his father’s books and seen Dr. Schaeffer’s film series. Francis Schaeffer, at the time, was the biggest name in evangelical Christianity and had, for all practical purposes, become somewhat of a guru to me. Indeed, Francis Schaeffer was one of the biggest influences in my life.

At the time, I was a struggling lawyer fighting cases on behalf of Christians—most of whom could not pay me. And my experience with evangelicals generally had been disappointing. Thus, I had come to the decision that it was time to return to a regular law practice. As far as I was concerned, I had given the religion business my best shot.

At the time, I was a struggling lawyer fighting cases on behalf of Christians—most of whom could not pay me. And my experience with evangelicals generally had been disappointing. Thus, I had come to the decision that it was time to return to a regular law practice. As far as I was concerned, I had given the religion business my best shot.

That’s when I received a call from Dr. Schaeffer’s son, Franky, as he was known then. Frank had read about some of my religious freedom cases. “I want you to work with my dad and me,” he said. That was late summer 1980.

Frank, the originator of many projects, challenged me that day to write a book called The Second American Civil War about the declining moral climate in America and how the courts had distorted the law. He wanted to be my agent, which meant that I could actually get the book published. Later, I changed the name of the book to The Second American Revolution. Published in 1982 (with an introduction by Francis Schaeffer), it sold over 100,000 copies. Soon thereafter, I founded The Rutherford Institute, and the legal arm of what Frank and I had been calling the “Christian Activist” movement was born. Many clones would follow in the coming years.

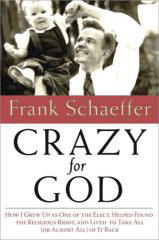

All of a sudden, I was back in the religion business and working side-by-side with Frank and his father. At the time, the Religious Right did not exist. Thus, Frank’s claim in the subtitle to his memoir, Crazy for God: How I Grew Up as One of the Elect, Helped Found the Religious Right, and Lived to Take All (or Almost All) of It Back (Carroll & Graf, 2007), is appropriate.

In fact, without the influence of Francis Schaeffer, who often was prodded into action by Frank, the so-called Christian Right of today would not exist. Dr. Schaeffer’s groundbreaking books How Should We Then Live? and Whatever Happened to the Human Race? set the tone and agenda for the emerging Christian Right. And without the philosophical groundwork laid by these books and A Christian Manifesto—for which I served as Francis Schaeffer’s research assistant—it is highly unlikely that people such as Pat Robertson, Jerry Falwell, James Dobson, Tim LaHaye and others would have had the political influence they wield. This despite the fact that much of what comes out of the mouths of these people would today alarm Francis Schaeffer.

The point is that I was there working with Frank and his father. Thus, I can validate what Frank in Crazy for God writes about their influence on religion and eventually politics in America.

During much of this, Frank was busy chipping away at the evangelical establishment in such books as Addicted to Mediocrity, Bad News for Modern Man, Sham Pearls for Real Swine and others. Always the iconoclast, Frank saw early on the weaknesses and hypocrisy so often evident in evangelical culture.

Francis Schaeffer died in 1984, and soon after, as Frank details in his book, his life began to unravel. And by the mid-1980s, because of the hypocrisy I had seen in the evangelical leadership, I began to recoil from the movement. But although Frank and I didn’t always agree, we continued to work closely through the mid-1990s.

In the meantime, Frank was making movies and writing some fine fiction. His later books include the best-selling Keeping Faith: A Father-Son Story About Love and the United States Marine Corps (2003) about his son’s military service in Iraq. He also co-authored AWOL: The Unexcused Absence of America’s Upper Classes from Military Service—and How It Hurts Our Country.

His latest book is Crazy for God, which to some hardcore Francis Schaeffer fans will come as a surprise and even a shock. Frank shares intimate details about his family that bring both Francis and his wife Edith down to earth. They were, after all, human beings, and that’s the way Frank describes them—as real people with real problems.

Crazy for God is a highly readable book. It is the journey of one person through the labyrinth of evangelical Christianity, one that Frank describes as a freak show. Agree or disagree, Crazy for God will stir debate.

I asked Frank some questions about Crazy for God.

John Whitehead: In your book Crazy for God, many evangelicals will have a problem with the fact that you raise some personal issues about your family. You basically say that your parents were rushing here and there being super-evangelicals and that they literally lost track of you and “forgot you existed.”

FS: That, in fact, is how it was. My sisters had a somewhat different experience because they grew up before my dad became any sort of evangelical figure. I was born in Switzerland and did my most formative growing during the years when Dad was busiest. Thus, my experience with our family is a little different than that of my sisters. I guess I would liken it to being the child of a presidential candidate. That doesn’t mean they were bad parents. When people are running for office, I’m sure their children tend to get lost in the shuffle.

JW: But yours weren’t running for office. They were living their daily lives.

FS: They were, but we were in a community that was a series of open homes. We literally had 30 to 35 people living in our house.

JW: At L’Abri.

JW: At L’Abri.

FS: Yes, at L’Abri. There were various chalets, but there were no dormitories as such back then, although there are now. Thus, basically I was living in a dormitory where I had my own room. But that was the only private space in the house, other than my parents’ bedroom. If I went down to the kitchen, for instance, to get a glass of milk, typically there would be five to six people sitting there talking to my mother and she would look up and nod. I would get what I wanted and leave. But the normal home life of someone living in a house, where they have a fair amount of time when they see their parents without other people around, really did not exist for me. It would almost be as if your parents were raising you in their place of work.

JW: How did that affect you?

FS: During my early teen years, it was very exciting because I was in a household full of 18, 19, 20 and 22-year-olds, hanging around with them. But the way it affected me long-term is that I am kind of reclusive in my adult grown life. When I got to the point where I could buy my own house and make a choice about my own lifestyle, I didn’t have many people over. I am someone who feels intruded upon when people show up unannounced, even if they’re old friends. I have a kind of knee-jerk reaction that makes me want to be as private as I can in terms of my own personal space. Also, as an artist and then a writer, I have chosen professions that make you spend a lot of time by yourself alone. I like being alone. If I would’ve had a different environment, I might be a little more of a social creature. But, as a matter of fact, I kind of enjoy isolation.

JW: In the book, you portray your mother as speaking down to her husband, the renowned Francis Schaeffer.

FS: Right.

JW: You also indicate that your father abused your mother.

FS: Right.

JW: Explain all that. I think it is important.

FS: Dad had a very strong temper. He and mother had a good marriage, in the sense that it lasted. They had a lot of affection for one another, and they were very dynamic. But there was also, as there are in a lot of human relationships, a very dark side. One of those dark sides came out when they were fighting. My father would yell and scream and throw things. Sometimes, it went beyond that. Basically what I talk about in the book is as much as I want to say about that. People can draw their own conclusions.

JW: You write in the book that your father, for example, threw plants at your mother.

FS: That was no secret. I’m sure other L’Abri workers knew that. Their relationship at times turned violent. There is no question about that, and I am not the only person who would know. The book in that sense is not an expose of that part of my father’s character. Living in the community of L’Abri with people in our house and other workers coming and going, there are plenty of people walking around the world today who either heard or saw things that would make them draw that conclusion. That was actually not much of a secret.

JW: Well, none of those people have written a book about it. People are going to say that you’re outing your parents. Some people almost worshipped your father and thought he walked on water. And now they’re going to be a bit disillusioned.

JW: Well, none of those people have written a book about it. People are going to say that you’re outing your parents. Some people almost worshipped your father and thought he walked on water. And now they’re going to be a bit disillusioned.

FS: There are two things here. First, if you’re writing a memoir, there is no point in doing it unless you’re going to be honest. Obviously, growing up in a family is a big part of your life experience. If my dad had been a steel worker in Pittsburgh in the 1930s or 40s and I had written a book set there, that is what it would have been about. It just happens that my father was well-known to a certain segment of the American public, which was the evangelical group. Wherever those people get their information about him, it’s going to be incomplete. I think the point of the book, from that point of view, is that when I am writing about my recollections, I talk about things that happened in my own life. I pretty much lay my cards on the table, and I do the same for other things I mention. And, of course, there are a lot of things one chooses to not include because you can’t put everything in a book. But, on the other hand, there was no point in writing anything unless I was going to try to be honest. I guess if there’s a wider lesson to be drawn from that, whether it’s rock stars, evangelical beaters, evangelists, presidential candidates or whomever, it’s that everybody is a human being. Anyone who looks at any human life and thinks it was all roses and was easy is obviously mistaken. This is true from what we all know about our own lives. Thus, in the case of my parents, from my point of view, I write about them honestly. I also write about them with affection. I think that anyone who reads the book will see that I was very fond of my dad and admired him in many ways. But there is no point in writing about someone unless you’re going to lay it out.

JW: But when people read that he was an abuser and was hen-pecked by his wife and that Edith and Francis competed with one another, how do you think it will affect their view of him and his work?

FS: I say some pretty unflattering things about myself in the book, too. If you read biographies that try to be honest about human life, you have to realize that we are all flawed. My parents were no better and no worse than anybody else. Essentially, there is nothing more or less valid about what Dad wrote because he was a human being. I think the only people who would look at his work otherwise are those who have a false impression of what Christian leadership is. In other words, they’re looking to someone’s life as an example of perfection, rather than what the person was saying, to see if it is true or false. They should know full well that everybody has that measure of hypocrisy in their lives; everybody has a measure of being flawed. My parents were no better or no worse. Thus, if someone who looked to my dad as a kind of a guru or someone who walked on water is disillusioned, they probably should be. But they shouldn’t only be disillusioned about him, they should be disillusioned about any idea of perfection in any human being because no one is like that.

JW: I quote from your book: “I believe that my parents’ call to the ministry actually drove them crazy. They were happiest when they were the farthest away from their missionary work. I think religion was actually their source of tragedy.” What do you mean by that?

FS: What has been interesting is discussing this book with my sisters. All three of them have read it, and they all have various ways of seeing things differently than I do. But I think we all agree that Mom and Dad were happiest when they weren’t in the work of L’Abri. That is a statement of fact, not a theological statement. It’s a statement about their personalities. It’s basically like saying Sean Connery is a good actor, but he just happens to be someone who didn’t enjoy making movies. It was always a big relief to Connery when the shoot was done and he could go home again and live a different kind of life. He didn’t like being on stage. This doesn’t mean that he is any lesser of a good actor. And my parents actually had very natural talents that pulled them in other directions. My mother always wanted to be a dancer and be in the arts, but she never achieved that. My dad really loved art history and was never happier than when he was wandering around places like Florence. And so my observations as a child and growing up with them are very simply that. They were happiest when away from their work and most unhappy when on the spot and doing what they were doing. Does that mean they had the wrong calling? Maybe, but I can’t judge that. All I can say is what I saw growing up.

JW: You write that you remember your dad screaming at your mother one Sunday. Obviously upset or enraged, he throws a potted ivy at her. Then he goes downstairs and preaches the gospel. Is this hypocritical?

FS: I don’t think so, no more than some other L’Abri workers whom I won’t name who have had marital troubles, left their wives and still go around talking about the value of family. We are all flawed, and we all have things that we do differently. I talked about Billy Graham in the book. Growing up, I remember Dad talking to Billy Graham on a regular basis. Dad told me that Billy was always telling him that he was afraid to die. Is it hypocritical for Billy Graham to go out and preach that you can have faith in Christ? I don’t think so. Human beings are only able to imagine and see what they can imagine and see. My dad was who he was. He did what he did. But I don’t believe the level of hypocrisy in his life was much different from anyone else. It only looks different if you’re putting him on a pedestal and expecting things from him that aren’t true about anybody.

JW: Billy Graham is on a pedestal, and he comes off pretty badly in your book. You portray him as a bizarre figure. Thus, is Billy Graham not the god that people think he is?

FS: I would put it a different way. There are no people who are truly god-like or perfect. We are all flawed human beings. But I will admit that although I do go after some people, the real point of the book is to reflect on what my memories are. The book recounts the point where various people touched my life as a child or as an adolescent or as a young adult or whatever it might be. Those are my memories. Other people have other memories. But to the extent that I include things in the book, to my best knowledge, they are true. Does that give a full picture of somebody’s life? Absolutely not. Nor does the book claim to do that. Certainly not for a tangential person like Billy Graham who wanders in for a few paragraphs and then isn’t seen again. These are all things I personally experienced, and these are my memories. Again, I think there are a lot of people in the evangelical and other religious communities who look to religious leaders for a special kind of almost deity or guidance on a kind of a guru stage-like level that nobody has. That is the way I would see this. I just don’t see it as picking and choosing between people. No one deserves the kind of adulation that a lot of religious leaders are given these days.

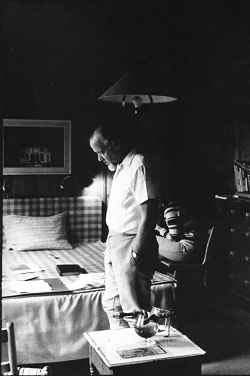

JW: In your book, you said your father could be screaming at your mother one minute and then muttering “I’m going to kill myself” the next. In fact, you write that your father contemplated suicide and spoke about hanging himself. Was Francis Schaeffer suicidal?

FS: I don’t know if he was really suicidal, but he was certainly depressive. My father spent big chunks of his life in very deep depressions, and, again, that is no secret. He talked about that in the context of L’Abri. He would also talk about it in the context of counseling people. He would say “I suffer from the same thing.” In fact, one of the reasons he was such a good counselor to individuals was that, unlike his public image that other people have fostered, he never held himself up to be that image. And in that sense, my father wasn’t hypocritical at all. He would tell people about his problems and say “I am in the same boat.” And that level of empathy is one reason that, on a one-on-one basis, he was one of the best counselors I’ve ever heard about or seen in terms of results of helping people turn their lives around. His empathy was real, and it came through, for example, when he would tell someone who had tried to commit suicide that he often contemplated it. That was a help to people precisely because he wasn’t holding himself up to something special. As I write in the book, I think my dad was a remarkably courageous man because he definitely suffered from chronic depression. He definitely had periods of time when he was thinking about killing himself or quitting or abandoning his faith. He talks about that very freely in the context of some of his L’Abri discussions with people. There were no secrets there, certainly in the context of individual counseling. That is not much of a revelation to people who knew him well, certainly not to his own children who saw him wrestling with very real problems.

FS: I don’t know if he was really suicidal, but he was certainly depressive. My father spent big chunks of his life in very deep depressions, and, again, that is no secret. He talked about that in the context of L’Abri. He would also talk about it in the context of counseling people. He would say “I suffer from the same thing.” In fact, one of the reasons he was such a good counselor to individuals was that, unlike his public image that other people have fostered, he never held himself up to be that image. And in that sense, my father wasn’t hypocritical at all. He would tell people about his problems and say “I am in the same boat.” And that level of empathy is one reason that, on a one-on-one basis, he was one of the best counselors I’ve ever heard about or seen in terms of results of helping people turn their lives around. His empathy was real, and it came through, for example, when he would tell someone who had tried to commit suicide that he often contemplated it. That was a help to people precisely because he wasn’t holding himself up to something special. As I write in the book, I think my dad was a remarkably courageous man because he definitely suffered from chronic depression. He definitely had periods of time when he was thinking about killing himself or quitting or abandoning his faith. He talks about that very freely in the context of some of his L’Abri discussions with people. There were no secrets there, certainly in the context of individual counseling. That is not much of a revelation to people who knew him well, certainly not to his own children who saw him wrestling with very real problems.

JW: In the book, you discuss an incident at L’Abri when your father walked in on you having sex in the nude with the woman who later became your wife. He just kind of walks away from it. Some evangelicals are going to wonder, didn’t Francis Schaeffer lecture his son on premarital sex?

FS: They may shake their heads in disbelief. But my dad didn’t take a moralistic judgmental angle. If it had been a L’Abri student, he wouldn’t have said anything. It’s not that he wouldn’t express opinions on sexuality, but Dad was just not that kind of judgmental person. He had a very strong moral chord but not in terms of a church-lady kind of response to that sort of situation with a teenager. This is one reason he was so effective in terms of the cross-section of people who came to L’Abri and would listen to him. He was different. He was not your typical evangelical pastor who was trying to protect his image. He was not ready to throw the first stone to maintain a public idea of sanctity or holiness. By the time you had been at L’Abri for a while and seen Francis Schaeffer, especially in the mid-to-late sixties, you were not seeing your typical evangelical.

JW: His views of homosexuality were quite different from those of today’s Christian Right, which is stridently anti-gay. But Francis Schaeffer didn’t see it that way. As you say in the book, he saw homosexuality as a serious matter. But he didn’t think they would stop being homosexuals if they became Christians. And he didn’t condemn them. Is that right?

FS: That is absolutely correct. A lot of people in the evangelical and fundamentalist communities speak theoretically about homosexuality being no worse than adultery or divorce. However, in practice, they are not undertaking national campaigns to single out evangelical people who were married to somebody else at one time and got divorced. So actually there is a tremendous moral hypocrisy there because the whole gay issue has been singled out for special treatment. My dad literally practiced what he preached. He said that homosexual sex was on the same level as adultery, premarital sex and spiritual pride. He didn’t differentiate between all this and write people off on the basis of it. He actually believed and acted on what a lot of people in the Religious Right say theoretically. But he literally was that way. My dad didn’t see it as a special problem to be singled out from everything else. He didn’t see it as threatening. We had quite a few gay people come through L’Abri. As a child, I knew who they were and why. But my dad did not push them into programs where they were going to try to become straight based on special counseling. He didn’t see it that way. He just saw this as one amongst all kinds of challenges that face people humanly and was very compassionate about it. We had a number of people who came to L’Abri who were not Christians or were Christians who were gay who never changed their orientation, and they didn’t become less friendly with my dad as a result. He didn’t make a big point of it one way or another. That is how his attitude manifested itself to other people.

JW: You talk about growing up and becoming a teenager. Then we get to the part that most evangelicals will be really interested in—where Francis Schaeffer becomes a worldwide figure with the How Should We Then Live? book and film series. But wasn’t this entire project your idea?

FS: I cooked it up with Billy Zeoli when he was visiting L’Abri. At that time, he was the president of Gospel Films. It actually took quite a bit of convincing to get my dad to do it. He saw it as a departure from what he was doing. But out of that came both the How Should We Then Live? film series and the book.

JW: And they were both great successes. I had just become a Christian in 1974 and started reading your father’s books. In 1976, I saw that film series. I had been around so many spaced-out Christians but then realized there were Christians who could think.

FS: Dad was unique for that, but I think people forget this aspect of his work. Later, when the Religious Right emerged, he was remembered for influencing that movement. But actually that period of time was very brief because, for most of his life, he was obscure and unknown. Then he became well-known because of the How Should We Then Live? project.

JW: Very well-known.

FS: Yes, very well-known. And most people were like you. What you have just expressed describes the feelings of the first wave of people who could be described as Francis Schaeffer readers, not followers. They were people like you who were interested in his work and were impressed by the fact that he was talking about philosophy and art history.

JW: I was impressed that he was talking about real things.

FS: And culture and music and he knew who Bob Dylan was.

JW: He was talking about real life, not just pie-in-the-sky.

FS: That’s right. And I’m hoping that my book, aside from humanizing dad, will also redeem his reputation as someone who was known for something better than simply being a leader in the Religious Right. He really was known as a thinker.

JW: Are you saying that Francis Schaeffer wouldn’t be part of the Christian Right?

FS: Yes. He has been used by people like James Dobson, Jerry Falwell and others to give some respectability to points of view that really were not his. What made my dad’s heart beat fastest was talking about people’s philosophical presuppositions and how they lived. He wanted to put people’s lives back together again, people who had problems. The politicized view of him is illegitimate.

JW: But you have to admit that your father helped change the face of evangelical fundamentalism. Before then, no one was involved. Then he did Whatever Happened to the Human Race?, which was the beginning of Christian Protestantism’s involvement in the abortion issue. Thus, evangelical opposition to abortion was really started with your father.

FS: That’s right.

JW: In fact, you and your dad spearheaded all that. You changed the face of evangelical Christianity.

FS: I talk about some of that in the book. But I can’t say that for sure.

JW: I can say it.

FS: What I can say is that there would not have been a Religious Right as it became known, including the make-up of the Republican Party, without the involvement of my dad, myself, Dr. C. Everett Koop, you and those of us who were in on all this at the very beginning. My book discusses some of the unintended consequences. My father never would have pictured a day when his work would help lay a foundation for the anti-gay, anti-homosexual campaign being carried out by people like James Dobson and others. Those were not his issues. They were not his concerns. Dad was very narrowly focused. The issues that got him, me and people like you involved were very narrowly focused. And it was Roe v. Wade and all the fallout that came from that court decision.

JW: In the early days, we never talked about the gay issue.

FS: It wasn’t an issue at all. My dad’s interests were philosophical. They had to do with history and apologetics. They had to do with individual lives and trying to help people put broken lives back together. This is what his focus was. Unintentionally, I think some of the activities we got involved with in terms of the film series basically became part of an enormous political movement. It helped lay the foundation for that and eventually put people like George W. Bush in the White House. In fact, people like James Dobson and Jerry Falwell had never been involved with politics or anything else like that before. Dad died in 1984 before some of this happened. But even before his death, he would never have imagined the direction all this would go in. But that is what happens with unintended consequences.

JW: You say in your book that your father thought these people were plastic and the people of the Christian Right were right-wing nuts.

FS: Yes. He would come out of meetings with some of these people, shaking his head. I have some very vivid memories about this. But he essentially justified his work with them as being co-belligerents on projects that were of enough importance to tolerate them.

JW: Would he be happy with the way they use his name today?

FS: Absolutely not. The idea of watching himself on The 700 Club or a replay of him preaching from Jerry Falwell’s pulpit would not please Dad, given the direction all this has gone.

JW: When your father was on The 700 Club once, he called me right after the show. He was so upset. He said, “Do you know what they did to me? I was on that show talking about all these important things such as abortion and other issues, and they followed me with Christian jugglers.” It blew his mind. He saw it as a crazy world, but he would see it as even crazier today.

FS: Yes. He saw it as a crazy world. He would say things like he thought Pat Robertson was out of his mind or that Jerry Falwell was harsh and inhuman. But he realized there were larger issues. Sometimes you work with people you disagree with because the issues are so important. You’re simply hoping to help. But the Francis Schaeffer I grew up with loved the arts. He was a philosopher. The idea that he was somehow a creature of the Religious Right is ridiculous.

JW: You note in your book that you slowly realized that the Religious Right leaders you were helping to gain power were not necessarily conservatives at all in the old sense of the word. They were anti-American religious revolutionaries.

JW: You note in your book that you slowly realized that the Religious Right leaders you were helping to gain power were not necessarily conservatives at all in the old sense of the word. They were anti-American religious revolutionaries.

FS: I personally came to believe that a lot of the issues that were being latched onto by the Christian Right, whether it was the gay issue or abortion or other things, were actually being used for negative political purposes. They were used to structure a power base for people who then threw their weight around. The other thing I began to understand is that in dismissing the whole culture as decadent, in dismissing the public school movement as godless, in talking about anybody who opposed them as evil, the Religious Right was only a mirror image of the New Left. Thus, the Religious Right and the New Left are really two sides of the same coin. What gets left out is a basic discussion about the United States and the reality of living here, the freedoms we enjoy and the benefits of a pluralistic culture where people are not crushing each other over beliefs. This gets lost. Thus, the kind of harshness you see in left and right-wing blogs today, for instance, such as it’s red state, blue state America, I just got sick of it. In other words, the Religious Right was as negative and anti-American as anybody I ever talked to on the Left. So the people we had coming through L’Abri in the late sixties and early seventies bashing the United States in a knee-jerk way over the Vietnam War was exactly the same kind of thing that you would hear in a different way from Falwell and Dobson and these other people.

JW: You argue in the book that such people want the world to go badly. They want the apocalyptic view to prevail—the idea that the world will be embroiled in chaos and violence.

FS: You are absolutely right. If, for example, you live in the Vietnam era and you don’t like the United States, you wind up rooting for the Viet Cong. You do what Jane Fonda did. You go to Hanoi and pretend they’re all good people, and you bad mouth your own side. The same thing happened with the Religious Right—that is, their idea was that without fundamentalist Christian beliefs being absolutely imperative for everybody in the country, the country would go to hell in a handcart and that would be the end of everything. So negative things were always accentuated. It’s like the local news channel that reports on the kidnapping of one child somewhere and plays it again and again and again until everybody is so paranoid that they think children are being snatched off the streets everywhere. But when you look at the real statistics, it doesn’t actually happen that often. America is a fairly safe place to raise a child statistically, no matter how it feels from the tabloid media. It’s the same thing with the Religious Right. By the time they tell you over and over about all the bad things happening, such as statistics on crime, teen pregnancy and so on, I begin to get the feeling that they don’t want things to get better. This is their shtick. This is the way they raise their money. This is how they maintain their central power base.

JW: Fundraisers for the Christian Right have told me that you can’t raise money on good news. The emphasis has to be on bad news.

FS: Yes. You’re exactly right. The anti-Americanism was very clear to me in that there is a group of people whose best interests are served by failure, not by success, when it comes to what is happening in this country. That was a reality as I saw it, and I still see it that way.

JW: In the sixties, L’Abri was vibrant and alive. It was a place where people could learn about culture and philosophy. Those great books from your father came out during that time. Then you say this all stopped when your father became involved with the Christian Right and returned to fundamentalism.

FS: Yes. I don’t think it was so much right-wing fundamentalism. But it was certainly the theological battles of the 1920s that he kind of left behind him—the big splits in the denominations with places like Princeton going liberal and the fights over inerrancy and all that. There was a huge chunk of his life where he left that kind of dynamic behind. It was not so much that he changed his mind but that it just wasn’t important to him anymore. He outgrew it. My dad moved on to talk about philosophy, music, culture, art and so forth. I look back on that with regret, thinking that it is a shame that he got drawn back into the fundamentalist orbit.

JW: You paint your family at the end of the day as dysfunctional. You say your sister Susan and her husband lived in an assisted living facility. Priscilla was on Prozac. You were in therapy. You had a problem with name identification—you kept changing your name.

FS: Right. The name change thing is somewhat trivial, but it is symptomatic of something.

JW: I didn’t know what to call you for awhile—Frank, Franky, whatever.

FS: The funny thing is that my sister Priscilla did the same thing. All of a sudden, we had to call her Prisca. We all had our own little rule.

JW: You write that Priscilla suffered from depression and anxiety attacks. She burned out early. What causes families to break down like that?

FS: First of all, I wouldn’t describe her as having broken down. I would just say that she is very straightforward about the fact that she was on Prozac. When I was writing this book, she didn’t care if I told everybody. I would tell anybody who came to L’Abri about my problems. And she actually thought it was a good thing to put it in the book.

JW: People, no matter who they are, have problems. James Dobson or Billy Graham, in other words, are not like Jesus.

FS: No, and neither was Francis Schaeffer. And Frank Schaeffer is not. If you peel back the lid of any household and really look at it, the question is: do any of us have the ability to really look at ourselves honestly? Obviously not, because you can’t spend your whole day on introspection. You have to go forward. But the fact of the matter is that I don’t think the Schaeffer household is better or worse than any other. I think it was different than a lot of other households in one sense. You could call it abnormal in that it wasn’t the normal “American upbringing.” But then you read a lot of memoirs and talk to a lot of people who have been in “normal households,” and they turn out to have their own problems as well. So I don’t think the Schaeffer children wound up worse or better than anybody else. The fact of the matter is that we certainly did not leave an inheritance in terms of psychological well-being that is better than anyone else’s or particularly great. In other words, we all have our problems, and that is the reality of it.

JW: You and your father changed the face of abortion in this country. But although you still regard abortion as a tragedy, you no longer believe it should be illegal. What is your current view on abortion?

FS: My view on abortion is the same that it has always been. Abortion is terrible. It’s a very bad legal precedent, which was set in Roe v. Wade. Having said that, I think the reality of the matter is that abortion now encompasses all kinds of other issues from experimentation on embryos to late-term, partial-birth abortion.

JW: Do you believe life begins at conception?

FS: Yes, I believe life begins at conception, both technically and morally. But I also think that in terms of the present American climate, we are not going to be able to have all the abortions outlawed. It is totally unrealistic to push for that. What we need to do is rethink Roe v. Wade. But we don’t need to roll it back in the sense of getting to a place where all abortions are illegal. Thus, my view on the legality question of abortion has changed. But I don’t think my view on the morality of abortion has changed.

JW: What do you think of George W. Bush as the Christian president?

FS: He is arguably the worst president in the history of the United States. He is unfit for the office of president of the United States. He has trouble speaking the English language and articulating a point of view. Second, he has led us into a war—in which my son, by the way, fought—on false pretenses. That is a terrible thing. Bush is personally responsible for the displacement of the Christian minority in Iraq. It was the last large Christian minority anywhere in the Middle East, and it has been destroyed. It is ironic that someone who proclaims he is a Christian president has single-handedly started a war that has undone the last Christian minority in the Middle East. Now it is wall-to-wall Islam from Tehran all the way to the Mediterranean with the exception of Israel. There is not one place outside of Syria that still has that intact Christian minority now.

JW: Are you opposed to the war in Iraq?

FS: Absolutely. We had a legitimate cause to go into Afghanistan, and it was the right thing to do. It was the only logical response to 9/11. But Iraq was a completely misbegotten fiasco from the beginning. It was unnecessary and will only make our world situation worse.

JW: Do you think it is ironic that the Christian Right supports the war and has raised very few moral questions about it?

FS: Yes. Because of my son’s service in the Marine Corps, I’ve written on the subject of who serves in the military and who doesn’t. There is no question about the fact that when you have the Religious Right, the neoconservatives and others supporting the war, it is hypocritical when you discover that there is no preponderance of their own children who volunteer and serve. This is a fundamentally immoral situation, especially when you have someone like James Dobson who could use his prestige to call for his followers’ children to volunteer and serve. They typically make the moral case for the war without anybody having to actually sacrifice for it. It puts an immoral blossom on the whole enterprise. Also, it would be something that I would think Christians would want to talk about, as well as the fact that a Christian minority in the Middle Eastern Islamic country has been destroyed.

JW: Obviously, your feelings about the Religious Right have affected your faith.

FS: My faith is a little more nuanced than it would have been at one time. I am certainly not a fundamentalist. I have a lot of questions and a lot of doubt. I try in the book to give a snapshot of where my own faith would be now, and pretty much that is where I would leave it. But in terms of the fundamentals of the Christian faith, I do believe Jesus Christ was the Son of God. Do I believe in God? Of course. That question should come first. Do I believe all religions have equal values? No, I do not. The further they get from the teachings of Christ, the less valuable they become. On the other hand, I don’t see myself as a fundamentalist because I read the Bible with a lot of questions about what is allegory and what is literal. As a child at L’Abri, I would not have had such questions. I would have just taken everything literally. I certainly don’t focus on the issues in the Old Testament of the creation of the world in six days versus evolution or creationism or intelligent design. None of these things interest me very much.

JW: Are you an evolutionist?

FS: Oh, I certainly believe in evolution. But I always have. Even my dad in the early days of L’Abri said he didn’t care whether the world was created 600 million years ago or 6 million or 6,000. He was very open to the idea of a kind of theistic evolution. Where I disagree with the Darwinian view is that I think it is too limited. How something happened is not an answer to why it happened. The why is because God created it to happen. That is an interesting subject, but my faith doesn’t feel threatened by the world being 600 million versus 6,000 years old. Those things really don’t interest me.

JW: Frank Schaeffer, what is your legacy?

FS: That is a very good question but one that I cannot answer because I’m still shaping it.

JW: Did you help ruin America or did you make it a better place to be?

FS: Good question. I think basically my legacy is that I am someone who took a long time to find out what he was good at, which centers in the arts and writing. Along the way, I did a lot of self-promoting that resulted in my being part of a political movement I helped start. I certainly wasn’t able to help finish it or even stay interested in being involved with it, however. So, I don’t know. I think I am a pretty typical American figure who has reinvented himself several times. And where that all goes, I don’t know. Right now, what I am interested in is trying to write as well as I can, and I look at this memoir as my next book.

DISCLAIMER: THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN OLDSPEAK ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE.