OldSpeak

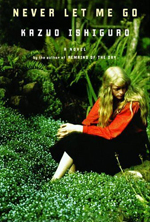

Book Review: Never Let Me Go

By Joshua Anderson

March 03, 2006

Writing a piece of fiction stacked with political and ethical implications is like pulling a block from the bottom of a wooden tower. It’s something to be done both carefully and firmly—moving slowly but finishing the job without giving the reader time to pause and think too much. From the reader’s perspective, in order for the story to be effective, it must first of all be a story, and it must be the characters and not the issues in question that drive the emotion of the plotted events. Though extensive debate over human cloning has thus far been postponed by cultural distaste for the issue, advances in science will one day almost certainly make the cloning of human beings both more realistic and more effective in helping extend the lives of the sick and elderly. As that day approaches, there is little doubt that real discourse on this issue must soon occur at every level of our society. Are there good reasons to ever create and kill human life in order to give life to others? What if human cloning held the key to ending cancer? Would the cloned life that was created even be human at all? In the recently published Never Let Me Go, Kazuo Ishiguro, a past winner of the Booker Prize, manages to navigate these tensions and deliver an often moving and ultimately successful warning against the possibilities and consequences of ethical decisions that will soon demand our society’s certain attention.

Writing a piece of fiction stacked with political and ethical implications is like pulling a block from the bottom of a wooden tower. It’s something to be done both carefully and firmly—moving slowly but finishing the job without giving the reader time to pause and think too much. From the reader’s perspective, in order for the story to be effective, it must first of all be a story, and it must be the characters and not the issues in question that drive the emotion of the plotted events. Though extensive debate over human cloning has thus far been postponed by cultural distaste for the issue, advances in science will one day almost certainly make the cloning of human beings both more realistic and more effective in helping extend the lives of the sick and elderly. As that day approaches, there is little doubt that real discourse on this issue must soon occur at every level of our society. Are there good reasons to ever create and kill human life in order to give life to others? What if human cloning held the key to ending cancer? Would the cloned life that was created even be human at all? In the recently published Never Let Me Go, Kazuo Ishiguro, a past winner of the Booker Prize, manages to navigate these tensions and deliver an often moving and ultimately successful warning against the possibilities and consequences of ethical decisions that will soon demand our society’s certain attention.

Never Let Me Go is narrated from the perspective of Kathy, a grown women who relates a series of memories of her childhood as a boarding student at Hailsham, an idyllic community of young people who are encouraged to explore their artistic talents in quiet isolation in the countryside of England. Kathy’s tone is both off hand and intimate, like a letter to a good friend or a private journal, commenting retrospectively on the events as she describes them. Her story has mostly to do with the normal happenings of adolescent life and especially her evolving relationship with Ruth, her strong-willed best friend, and Tommy, the social outcast who becomes Kathy’s friend and eventually Ruth’s lover. Kathy tells her story in chronological sequence, beginning with adolescence and moving toward adulthood, but in the midst of this she also often recalls events from her early childhood (also at Hailsham, where she has always lived) as well as providing glimpses into her current adult life. The effect of this narrative technique, which creates and fills gaps in the reader’s knowledge, soon causes the reader to realize that all is not quite as innocent as it first appears in this fictional world. Only slowly is the reader able to fill in the horrifying details.

Quiet boarding schools typically prepare children of the upper class for successful and luxuriant lives. But Hailsham is different. Indeed, the children themselves only slowly begin to realize what it is they are being readied for. When one of the Guardians (sort of a cross between a teacher and school parent) grudgingly explains why Kathy and her classmates must never smoke, she puts it this way: “You’re…special. So keeping yourselves well, keeping yourselves very healthy inside, that’s much more important for each of you than it is for me.” Afterwards, as an adult, as Kathy recalls the event, she wonders: “So why had we stayed silent that day? I suppose it was because even at that age—we were nine or ten—we knew just enough to make us wary of that whole territory. It’s hard now to remember just how much we knew by then. We certainly knew—though not in any deep sense—that we were different from our guardians, and also from the normal people outside; we perhaps even knew that a long way down the line there were donations waiting for us. But we didn’t really know what that meant.” At this point in the story, the reader knows about as much as the 10-year-old Kathy does about her future, and because these words are shrouded in mystery, their effect upon the reader is multiplied.

The picture that slowly emerges is one of an alternate world (the book is set in “England, late 1990s”) where the promise of genetic cloning has been embraced by society at large, and organ production is overseen by the government and has been instituted by law. Western culture has decided that the ability to cure terminal diseases like cancer is well worth the price of creating cloned children for the sole purpose of organ donation, and Kathy and her friends are destined for an innocent childhood nurtured with the best that England has to offer, and then, a nightmare. Once their bodies are mature, they will be first “carers,” looking after other, older “donors” in between operations, and then finally “donors” themselves. This is what it means to be “special” in this society: the luckiest of them will live for three or four “donations,” but most only one or two, and very few until their thirtieth birthday. The children slowly awaken to this knowledge about their lives: they are both “told and not told”—but as they grow older, they do not protest or complain, but rather embrace their fate with passive acceptance in its normalness, unwilling or unable to fight a horror to which their society has long ago grown both inoculated and addicted.

Surprisingly, the main tension throughout most of the book does not come from the long shadows cast by the future of Kathy and her friends, but rather from their normal human longings and struggles. Kathy and Ruth are longtime best friends, but their friendship with each other is complicated when Tommy enlarges their relationship into a triangle. Their story of friendship, lies and floundering toward love is one that is both familiar and foreign—one heard before but now changed because of the strange backdrop that Ishiguro has created. Ultimately, it is the love that emerges from their tangled web that rises to challenge the prevailing wisdom of the culture around them and shatters the contradiction of a system of death created to prolong human life—a love whose plea to survive is expressed with as little adornment as the book’s title. Kathy, Ruth and Tommy expose the cruelty of the utopia they serve with the blunt weapon of their humanity. As they draw, dance, weep, lie, hope and make love, they slowly name the danger that faces our own world as it begins to lurch toward gigantic decisions regarding genetic cloning and the price of life itself. In Ishiguro’s world, the system may continue to march on without stopping for the longings of a few lovers, but it does not march unscarred. One of the contemporary debates in academic and religious circles today is over whether cloned humans would still have souls attached to their bodies. In the fictional world described in Never Let Me Go, that question has been answered emphatically, and after dwelling for a while there, any reader with half a soul himself can hardly wonder anymore about the question in our own.

DISCLAIMER: THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN OLDSPEAK ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE.