OldSpeak

American Fundamentalists: Christ’s Entry into Washington in 2008: An Interview with Joel Pelletier

By Nisha N. Mohammed

July 05, 2006

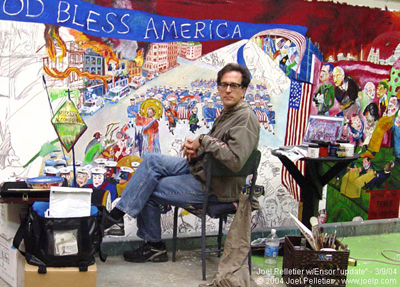

Joel Pelletier is a self-proclaimed “multimedia artist” whose satirical painting “American Fundamentalists: Christ’s Entry into Washington in 2008” has raised a few eyebrows for its controversial portrayal of the Christian Right.

Concerned about the growing influence of Christian fundamentalism in American politics, Pelletier was inspired to create a contemporary version of Belgian expressionist painter James Ensor’s 1888 painting “Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889,” which is housed at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. Attempting to convey the hypocrisy of using any and all events to assert one’s own self-importance, Ensor mocked the elites and government officials of Belgium and France by painting Christ’s return as a free-for-all party. Likewise, in his take on Ensor’s political satire, Pelletier depicts (in his own words) “current American religious, corporate and political fundamentalists and their lackeys whooping it up in a big parade celebrating the return of Jesus, as 2008 Washington burns, the sky is a permanent red, and everywhere snipers and military aircraft stand guard.”

Pelletier spent months researching Ensor and studying the various techniques used in “Christ’s Entry into Brussels” before he started to put paint to canvas. Pelletier incorporated more than 100 historical figures, politicians, televangelists, Christian and political activists, celebrities and other notable figures in his visual commentary on the merging of Christianity and politics in the United States, including John W. Whitehead, president of The Rutherford Institute. The finished work, which measures 8’ 4” x 14’, made its public gallery premiere at the Lankershim Art Gallery in North Hollywood, Calif., in July 2004, and has been on the road since then. Pelletier also makes himself available to participate in lectures and panel discussions on the topic of “American Fundamentalism and the Threat to Democracy and Freedom of Faith.”

Pelletier attended Hartford Art School while working toward a degree as a classical composer at the University of Hartford in Connecticut. Currently, Pelletier continues to hone his diverse interests in art while working as a web consultant and graphic designer.

Pelletier agrees that “the strength of our country and culture is the Constitution.” However, he insists that “we are a nation of laws founded on Greek Philosophy, the Enlightenment and the Magna Carta, not the Bible or the Ten Commandments.”

In this interview with OldSpeak, Pelletier talks about his painting “Christ’s Entry into Washington in 2008,” his rationale for the portraits he chose to include—including John Whitehead’s—and the message he is hoping to communicate.

Nisha Mohammed: How long did it take you to put this painting together?

Joel Pelletier: I had been thinking about it on and off for three to four years. I spent about a year of regular research on the individuals, movements and groups. When I actually started the physical painting of the piece in January 2004, I averaged five to six hours a day, five to six days a week, with another two to three hours at night reading and speaking with the different folks in the movement. That went on for a little over five months. The painting actually took about six months to complete.

NM: Are there any individuals you included in the painting that you would choose not to include now? The subtitle of the piece is “Christ’s Entry Into Washington in 2008.” It makes a definite statement about a movement toward a Christian theocracy.

JP: You have to compare it with James Ensor’s painting “Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889” and contrast it with the whole concept of Armageddon and Rapture that is rampant in fundamentalist Christianity today. These concepts only started to exist in England and parts of the United States by that time and were created by John Nelson Darby and a few other folks. What we are dealing with in the Ensor painting is a very strictly celebratory Mardi Gras-style parade celebrating the return of Jesus. He was trying to make his own statement and complaints about the status-quo and the political and religious establishment at the time.

Ensor was never allowed to show it. Also, I am contrasting that with what is now the current pop interpretation of the End Times, Armageddon, which is heavily influenced by Tim LaHaye and his Left Behind movement. Also, a number of others in my painting got that whole ball rolling a lot faster in the ‘60s and ‘70s. It’s gotten to the point that we see today many saying that the Bible predicts there are going to be wars. It will be terrible. Millions of people are going to die in fires. Jesus is coming down with a sword and will throw people into Hell. To them, this is wonderful. Then we have the thousand-year reign for the Christian Right. How could anyone think that is good? How can any compassionate person think that the story told in that way can be something to celebrate?

By the way, what I was trying to do in the painting was show that this isn’t good. It is an awful idea. And whether or not it can happen, whether or not it’s true, it influences how people think about the world and influences their actions from day to day.

NM: You seem to be specifically speaking to and targeting religious extremists, particularly Christians, in your painting.

JP: I don’t believe that everyone in the painting shares, for example, the same views as people like John Whitehead. There are some that I consider very fringe groups, dominion reconstructionists and the whole Armageddonist movement, which are only a small part of this. The painting is a kind of “What if that is what happened, how would it look?” scenario. But my concern is fundamentalism.

NM: But if you really are going after fundamentalism, that could apply to anyone on either end of the spectrum.

JP: I am going after three particular branches of fundamentalism that have converged at this moment in time into the far right. It is a political fundamentalist philosophy of a single party government where they would run everything. And if anyone disagrees with them, they are un-American and unpatriotic. That very easily defines the far right of the Republican Party that is running the government at this time.

I am willing to accept that some people have a hard time with the word fundamentalist used in any context other than religious. Those running the fundamentalist movement are only a small percentage of the whole. Each of these folks, I believe, represents five percent. Most people are mainstream, middle of the road, and are trying to live their lives, raise their kids and be friendly to one another. But this very radical fringe movement, which on the very far end is typified by R. J. Rushdoony, Gary North, Pat Robertson, Jerry Falwell and James Dobson, is running the show.

The rhetoric from the extreme Christian Right on the idea of the Christian nation and biblical law is very dangerous. When it is combined with a political group, it becomes even more dangerous. And it is very dangerous for all Americans because it has the potential to destroy a society of laws based on the Constitution.

NM: Some of the generalizations you’re making could just as easily be applied to anyone on the extreme left of the spectrum. You almost need a parallel painting in some ways.

JP: I welcome someone to do that. I did my painting to make my point.

NM: But you’ve made some large generalizations by including all these people.

JP: That is part of art. This is not an academic thesis or paper. It is not a journalistic exercise. It is a piece of art. And I believe that I have actually been pretty reasonable. Except for maybe two or three individuals, I was very straightforward in my portrayal of the people as just plain human beings.

NM: But it is clearly a religious, political and social statement.

JP: That is kind of what converged. At no time in American governmental history have there been such ties between any large religious movement and the Executive branch of government. I feel that is a major development.

NM: It also had to do with the quest for religious freedom and was a reaction against a state church.

JP: It was a reaction against a lot of things. Many had some bad experiences, for example, growing up in what was basically a theocratic Massachusetts. But now we may be coming full-circle. As far as religious freedom and the diversity of religion, I believe these are also in jeopardy. I think the separation of church and state protects religion much more than it protects the state. That is a discussion we never hear any more. It is all about pushing in the other direction.

NM: How does Mel Gibson fit into the painting?

JP: Throughout Mel Gibson’s career, he has had a major Christ complex. He has a very narrow version of Catholicism. Much of what Gibson supposedly believes was totally discredited by the Catholic Church. And Gibson’s incredible success in involving the fundamentalist Protestant Church in his movement, as represented by his film The Passion of the Christ, is not, to me, positive.

NM: How have you represented African-Americans in your painting?

JP: There is Alan Keyes. There is Armstrong Williams and former secretary of state Colin Powell. I have placed people in the painting who I feel have the most effect on the particular movements that they are representing.

NM: What about the media?

JP: Media figures are very important. That is why there are so many media people in the painting. I’ve placed a lot of prominence on that. Indeed, a lot of what is called news and journalism today would have been laughed out of the room 30 years ago.

NM: But are some of these developments because we are a much more diverse culture now than we were 50, or even 100 years ago?

JP: This is a different time than it was 100 years ago. But I didn’t live then, and neither did you. What matters is where we live now. I honestly believe that a lot of what is going on in the painting and the people I portray in the painting indicates that diversity isn’t that strong in America anymore. We live in dangerous times. This is not where we need to be, and I am going to fight it.

NM: What you are talking about is not where either The Rutherford Institute or John Whitehead is coming from.

JP: I am not saying that. John’s inclusion in the parade was based on his earlier association and some of the things in which he was very active in the ‘90s.

NM: Thus, it is guilt by association?

JP: Yes. But there are other people in the painting who are like that. I don’t think Colin Powell represents any of the fundamentalist groups I discussed. But he is in an enabler and he took his orders, so he is also responsible. I put fear in his face. He is the only one in the painting who seems to think that all this isn’t the greatest thing in the world. But he still salutes it. Not everyone on the painting is a mover and shaker. I don’t believe that anybody on the canvas is necessarily an evil person per se.

NM: Can you describe your experience with The Rutherford Institute, and how you connected John Whitehead to the Christian Right?

JP: I’ve found the Rutherford website to be very informative and have enjoyed some of the stuff on there like the interviews. From my understanding, John Whitehead’s positions have changed or evolved. I don’t know for sure, but he certainly was associated with a lot of the people who were the movers and shakers who were responsible for the making of the Christian Right. Also, you can’t control how people decide to interpret you and your work and then move on with it. Nobody can. I get e-mails from people who are somewhat puzzled or upset that Francis Schaeffer, for example, is included in the painting. But there are plenty of references that you can find by simply doing a Google search that show a lot of very virulent, violent anti-abortion groups use him as one of their founding fathers.

NM: Regarding John Whitehead, or Francis Schaeffer for that matter, there tends to be more misperception about their positions on issues than what their writings actually promoted.

JP: That is probably not only accurate, but it goes all the way back to the teachings of Jesus in the Bible. There are a lot of people who would prefer that Jesus be the violent soldier who is portrayed by people such as Tim LaHaye. The guiding principle of many of the followers of Jesus is “turn the other cheek.” Look at what is going on right now with the Quakers and one of their famous members who went to Iraq. These folks went to war-torn Iraq knowing that their lives were in danger. But they went anyway.

NM: As John Whitehead constantly reminds us, the First Amendment is about freedom for religion, not freedom from religion. There is a grave misunderstanding about the so-called separation of church and state. Often, in many of the cases in which The Rutherford Institute gets involved, there is usually a government entity misinterpreting the First Amendment and prohibiting individual expression of religion. That’s completely different from a government entity enforcing one particular religion.

JP: We are not disagreeing.

NM: At a certain point, your painting looks like an artistic rendering of Hillary Clinton’s so-called vast right-wing conspiracy.

JP: Sure. I even put that on my site. What I am doing here is illustrating Hillary Clinton’s great right-wing conspiracy.

NM: This is interesting because I know that the vast right-wing conspiracy concept arose out of the lawsuit that The Rutherford Institute was involved in over Paula Jones’ sexual harassment suit against Bill Clinton. However, although Hillary tried to tie the Institute into the heart of the right-wing conspiracy, we actually had no ties to any of the other individuals.

JP: It doesn’t matter if you don’t have any other ties if, by your actions, you enable them.

NM: By our actions, we were doing what a lot of the people on the left should have been doing, which was holding someone accountable to not sexually harass an employee. It was a women’s rights issue—human rights issue—for us.

JP: I am not in any position to comment on the Paula Jones case and about the validity of the case one way or the other. But you certainly have to admit that there were plenty on the other side who were making a case that it was all trumped up.

NM: This is not a debate on the Paula Jones case or the merits of it at all, although I don’t know that anyone could have envisioned The Rutherford Institute becoming involved.

JP: And I am not suggesting that.

NM: Or could anyone have envisioned Clinton lying in his deposition?

JP: I agree. But, in the end, it was all that those who wanted to get Clinton had. They then tried to use the deposition lie to get him out of office, tied up $40 to $60 million of taxpayer money and years of time.

NM: Clinton could have resolved it pretty quickly at the beginning.

JP: Yes, but he is a human being, too. I am not going to defend Clinton. For progressives and liberals, Clinton was a major disappointment.

NM: Would you say, though, that everyone on there is supportive of what is happening?

JP: No. I believe that everybody on the canvas is supportive of their own particular agenda.

NM: Did you find that the painting opened up a dialogue?

JP: Absolutely. What the painting did primarily, which is what any work of art should do, is change the person. I am a different person now because of all the research and education that I put myself through. Then there were all the minute decisions that you make from moment to moment as you are planning it out and putting paint to canvas. As much as I feel that I was cursing many of the people I represented on canvas, it promoted growth for me as a person and as an artist. It has also allowed me to tour around the country and speak with people about these issues.

NM: In the articles on your website, you say that information is power and “this painting is my way of fighting back.”

JP: Part of this painting was an exercise in asking myself, “Am I deluding myself to think that just because I spent all this time learning more and more about the groups and the people that I was portraying on the painting that I am stronger for it and I am in a better place for it?” In the end, this is what art is all about. It is about exploring. It is about searching. It is not necessarily about discovering final answers.

I believe in absolute freedom of the press. I trust what I have seen on The Rutherford Institute website, what I have read and the people who have been interviewed. I like what you are doing. And I am honored to be included in that in any way I can.

To see more of Pelletier's painting, visit his site here.

DISCLAIMER: THE VIEWS AND OPINIONS EXPRESSED IN OLDSPEAK ARE NOT NECESSARILY THOSE OF THE RUTHERFORD INSTITUTE.